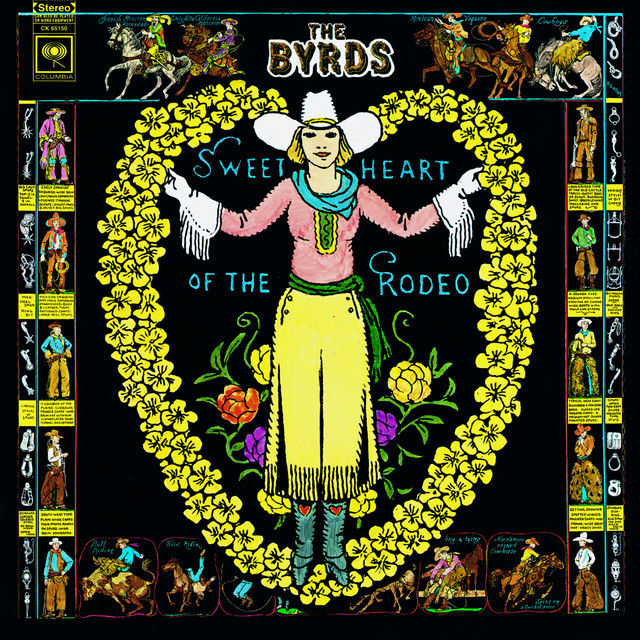

The Byrds - Sweetheart of the Rodeo

- Abigail Devoe

- Aug 4, 2025

- 19 min read

The deposed kings of the Sunset Strip got together with a Florida boy to blow the freakin’ lid off country rock with Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

The Byrds:

Roger McGuinn: lead vocals, acoustic guitar, banjo

Chris Hillman: bass, lead vocals on “I Am A Pilgrim” and “Blue Canadian Rockies,” co-lead vocals on “One Hundred Years From Now,” acoustic guitar, mandolin

Kevin Kelley: drums

Gram Parsons: acoustic guitar, keys, lead vocals on “You’re Still On My Mind” and “Hickory Wind”

Guests: Lloyd Green, JayDee Maness: steel guitar; John Hartford: fiddle, banjo, guitar; Clarence White, guitar; Earl P. Ball, piano; Junior Huskey, double bass

produced by Gary Usher

art by Jo Mora

“Historically, there has been no stronger trend in the pop music of 1967 than the emerging acceptance of country music and the passionate courtship between country and rock-and-roll. We can probably expect our trend-desperate, fad-hungry, youth-chasing mass media to go after the country frenzy the way they did the rock scene. We hope they’ll get started now, not be five years late and then over-correct.”

quoted from: Robert Shelton, “A New Love Affair: Rock and Country.” New York Times, 12/10/1967.

“What?”

“No no no, man! 1967 was the year of turning on, tuning in, and dropping out! It was about lighting guitars on fire and expanding minds, not that stupid hick shit. Country’s got nothing to do with rock-and-roll, it’s the music of the enemy! What the hell did country music have to do with the Summer of Love?”

At the same time as Robert Shelton's baffling New York Times piece, the Byrds were in the throws of a lineup crisis. In the fall of 1967, David Crosby was ejected from the band. He’ll be fine, he links up with new bestie Stephen Stills. The three-piece Byrds were not fine. Gene Clark briefly filled in for Croz, but since a main reason for Gene’s departure was his fear of flying, he wasn’t exactly much help for tour. The Byrds were losing crucial gigs. In December, their residency at the Whiskey was cancelled in favor of the hot new thing, Big Brother and the Holding Company. Then, three Byrds become two: drummer Michael Clarke left. Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn were freaking the fuck out. They could be a three-piece, but two was out of the question.

They finished The Notorious Byrd Brothers, with Chris’s cousin Kevin Kelley as drummer. But if they wanted to properly move forward as a band, they simply need more man power.

The Byrds were being pulled in two different musical directions. Roger wants to go jazz. They were founding fathers of psychedelic rock with “Eight Miles High.” But the lineup was in such turmoil through 1967, the bandwas left in the dust by the movement they helped found. Chris, on the other hand, was sick of being a rock-and-roll star. He gravitated towards country; see “Get To You” and the Byrds’ recording of “Wasn’t Born To Follow.” Something’s gotta give.

Enter. Gram. Parsons.

The son of an orange orchard heiress and an alcoholic war hero, Florida boy Ingram Connor (Parsons was his stepfather's last name) was practically born to be famous. He had the charm, the charisma, he's not exactly my type but he did have the looks! Women wanted him and men wanted to be him, he was a people magnet. He had big ideas, including his “cosmic American music:” a mythic blend of rock-and-roll, bluegrass, folk, gospel, soul, R&B, and country.

In 1967, Gram arrived in LA with his International Submarine Band. As the story goes, he bumped into Chris Hillman at the bank. They knew of each other and hit it off right away. In February of 1968, Gram debuted as a Byrd. He was their piano player...for about two seconds. He could hardly play piano. You could never make a movie of Gram’s life because audiences would complain about his ridiculous plot armor!

Case in point: the dissolution of the International Submarine Band. Upon joining the Byrds, Gram waltzed right into Submarine manager Lee Hazelwood’s office and announced he was with the Byrds now and would no longer work under Lee. Lee reminds him, “Hey Gram...you signed a contract. I’m not just gonna let you go!” He’d have to relinquish the rights to the International Submarine Band name and all royalties, from him and his bandmates, of their album. Lee didn’t actually think Gram would say yes to something so insane. But in the heat of the moment, he did! Lee snagged the rights to the band name and the album, and didn’t actually release the Band from any pre-existing contract. This will be important later.

Since Gram was a trust fund baby, he never had to worry about money. He didn’t have the foresight to see he was screwing his band over. In the words of Gram biographer David Meyer, “...he left his former bandmates unable to tour as the International Submarine Band, with no way to support their own album. Gram’s money protected him from the consequences of his whims; his bandmates had to pay the price of his folly.”

Meanwhile, Roger has this wacky idea for a concept album: a double album telling the story of the history of the twentieth century in music. Very SMiLE vibes. But he didn’t actually have songs, and neither did Chris. This leftthe door wide open for Gram to present his own material; both covers and originals. Chris was chomping at the bit to do country. Roger says “Why the hell not? What’s the worst that could happen?” And Sweetheart of the Rodeo is born.

The album was to be produced by Gary Usher, who produced the last two Byrds albums, and engineered by Roy Halee and Charlie Bragg, who worked with Simon and Garfunkel and Dylan respectively. First on the docket was “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” They had to get it done first and fast; they needed a single for country radio DJ Ralph Emery’s show that week.

The show didn’t go well. These are folkies, plus one Gram Parsons, in a pop band. Who are they to record this stuff? They don’t know nothin’ about real country!

So began the reception of the new Byrds: rejected by country purists, left behind by Byrds fans.

Over and over again in my research, I expected my preconceived notion that the country Byrds were crucified by the music press to be proven right; especially surrounding their fabled Opry gig.

Instead, I read lukewarm review after lukewarm review. This iteration of the Byrds was just fine. This response was due in part to bizarre sets; half-old stuff, half-new. From one gig at Ciro’s in Hollywood, “The sounds were distinct and at times it seemed as if two groups were playing, not one.” Their reception in Europe was a little better. They just don’t have the deep cultural context of American country music over there that Americans have. Sweetheart received good reception from critics at the time. They were acclimated to this new back-to-basics thing; see critical darling Music From Big Pink. But compared to the stronghold the Byrds once had on pop music, Sweetheartdidn’t just flop. It crashed and burned.

Fans weren’t expecting this from the Byrds, the guys who singlehandedly put the Rickenbacker on the map. And you have to consider what was going on in the country at the time. To the Byrds’ counterculture audience, buying albums by the Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother, country music was seen as everything wrong with America. Music for stupid hicks. Roger said, “Our fans were heartbroken that we’d sold out to the enemy. Politically, country music represented the right-wing redneck people who liked guns. We were the pioneers—with arrows in our backs.”

To add insult to injury, by the time the album dropped, Gram had already quit the band!

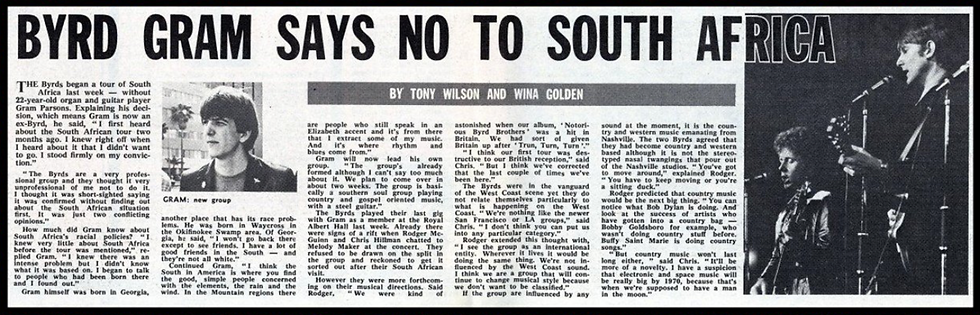

In July of 1968, the Byrds stopped in England, where Gram linked up with his new bestie Keith Richards. After this, the Byrds were to tour through Africa. Including South Africa. British rock-and-roll musicians, like the Stones, had a hard-line stance about not playing to segregated crowds in South Africa. Roger and Chris decided to play there anyway; to try to break down that barrier with the power of their music. Promoters assured the Byrds that their crowds at our shows would be integrated, but friend of the band Hugh Masakela told them the Afrikaner white majority rule would never allow it.

It seems Gram saw the writing on the wall, if a little late. At the last possible moment – I’m talking as they were loading up gear to drive to Heathrow – Gram backed out of the tour.

For years, Roger and Chris were bitter over this. They already weren’t on the best footing to begin with: Roger felt he was losing control of his band to an impulsive rhinestone-wearing doof. The guys alleged this was all a selfish stunt so Gram could keep hanging with the Stones. Roger even accused Gram of “paint(ing) (him) as a racist. It was a dirty trick.”

The rest of the Byrds went on to South Africa, facing huge backlash on both sides. They stated to South Africanpress they were against apartheid and got threatening phone calls daily. Music press in Britain and the States thought it appalling they’d still go to South Africa at all. Nat Hentoff for Jazz & Pop tore into the Byrds for going through with it:

“Parsons said...the group, ‘are a professional group. They thought it very unprofessional of me not to go to South Africa.’ It is considered ‘professionally’ correct for scientists to engage in research on chemical and biological warfare. It is considered ‘professionally’ correct for lawyers to work on corporate interests, no matter the social harm those interests cause. And the writers on the Times are regarded as ‘professionals’ by their peers...even though the Times is a chronic distorter of the news. To make the South African apartheid scene, as the Byrds did, is to be a traditional careerist. The good soldier...I’m not saying, of course, that rock music has to be political or social to be ‘valid’ and ‘relevant.’” But, “As the bread gets bigger – with all the attendant ‘professionalism’ required when the material stakes are higher and higher – are they going to just go along in the ‘professional’ manner of the Byrds?”

quoted from: Christopher Hjort and Joe McMichael, So You Want To Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day, 1965-1973 (2008.)

Son of a bitch, this Nat guy predicted all the hippies selling out to be good little capitalists come the ’80s! Anyway, Gram left the Byrds over this. Once again, Roger and Chris were left scrambling to finish an album by themselves. The surviving Byrds, they have a complicated relationship with Sweetheart. While Roger and Chris resented Gram for the Africa thing and the shit he pulled after, they’ve come to accept the country rock pioneer label. They performed for its fiftieth anniversary in 2018. Chris sold Sweetheart merch on his website. Thisalbum did set Chris on the trajectory he’d be on for the rest of his career. It’s continually lauded as one of the most influential records of the 60s; with Big Pink, Revolver, Pet Sounds and the like. It’s on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list.

So what changed? What happened to make commercial failure Sweetheart to one of the most significant albums in rock-and-roll history?

This is not hyperbole, this is not an exaggeration. Garth Brooks happened.

As grunge rose and fell, leaving behind...whatever that was...R&B had its moment, the boy band phenomena took over pop, and hip-hop officially arrived in the mainstream, country went pop.

One of my fondest memories is being back home and getting up early to put the last coat of dye on my purple sandals. My grandpa had just been in his shop so the radio turned right on, and was playing Hank Williams...Sr. Whether it’s his shop radio, the one in his garage, or my grandma’s car radio, unless they’re hanging out with me all they listen to is country radio. They grew up in rural America in the 1950s and early ’60s, that’s what they grew up listening to. My mother grew up in the same community. So did I. By the time I was a kid, it was thetail end of the country crossover boom. Of course, the men. Garth Brooks, George Strait, Toby Keith. But the women ruled the decade. Trisha Yearwood, Sheryl Crow, Shania Twain, Faith Hill. The Dixie Chicks. All that’90s country was inspired by the country rock boom of the 70s. The Eagles. Bonnie. Linda. Gram.

The last time I was home, I was listening to my grandpa’s go-to Sirius XM station with him and went, “My god! I hear Gram all over the place!” It’s the use of electric guitars. Sheer prominence of steel guitar. Believe it or not, before Sweetheart, Nashville used steel guitar pretty conservatively! Lloyd Green recounts asking the Byrdshow he should play, and the guys said in unison: “Everywhere.” Lloyd was shocked. You just didn’t do that back then!

()

And, of course, the look. There were no rhinestone cowboys before Gram Parsons!

What still deters people from Sweetheart?

1. For a rock-and-roll listener, to think of this…

...and this…

...coming from the same band is jarring. It kinda isn’t the same band anymore.

2. People writing off the whole country genre. I run into people who think all of country music ever is a monolith and all its listeners are stupid rednecks. With the current politics of country music...I honestly get it.

And 3. the matter of Gram’s voice. Pick a key, any key!

The latter really isn’t a problem for me. My continuing philosophy is that expression usurps technique, any day. As put by the world’s biggest Burrito-Byrds fan, Pamela Des Barres, Gram “felt everything so deeply, and to me, that’s the purpose of any great art. To feel, to share human emotion, to remind us we’re all on this sweet, spinning stewpot of a planet together.”

Back in October of 1967, Albert Grossman got ahold of recordings Dylan made in Woodstock. He brought thosetapes to London. Manfred Mann of all people got first pick, recording “The Mighty Quinn.” This would be the first recording by another artist of what we came to know as The Basement Tapes. The Byrds and Dylan always had a special relationship. A Dylan cover was what first put the Byrds on the map. And, save for Fifth Dimension, every Byrds album since had a Dylan tune on it. Albert sent the tapes to Chris, who passed them on to Roger. He picked “Nothing Was Delivered” and You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere to record.

The Byrds changed very little from Dylan’s original arrangement. I can even hear where the Byrds’ harmonies would slot in!

The latter would be the first song the Parsons-era Byrds cut for Sweetheart. Steel guitar player Lloyd Green came up with that instantly-recognizable opening lick. The tone is set for country rock. Country influence is felt through soft, clicking drums, and steel guitar filling the place a Rickenbacker might. It also comes from the players’ discipline and composed, yet easy mood. A misconception I saw surrounding my Big Pink review was that I thought that album was a totally naturalistic effort, there was no studio wizardry behind. I don’t think that, and there was studio wizardry, I literally said both! The studio attitude in LA by this time was loosey-goosey. It’s part of how psychedelia happened. There was a learning curve with Gary Usher and the Byrds recordingSweetheart. They were totally out of their depth with how the Nashville studio system worked; strict, fast, by-the-book, and before noon. These guys didn’t even get out of bed until 11:30! Though the vocals were dubbed inafter the fact (Nashville recording technology was archaic compared to LA,) the musicians are tighter on Sweetheart. They have to be or it’ll show with the psychedelic paint stripped off. It takes a straight back to lean back in the chair without falling over.

The bridge between rock and country is the airy organ. The rock-and-roll is Roger’s voice, as he does his best Dylan voice. His inflections on, “Buy me a flute and a gun that shoots” reminds me of “I took his fluuuute” on Dylan’s “I Want You;” a moment in an otherwise-great song I’ve been laughing at for years. Rog’s “Now Genghis Khaaaaan” especially gets me – Dylan doesn’t sing it like that on his recording! The signature Byrds harmonieshave diminished since harmony guru Croz took flight, but they work for Sweetheart. Chris’s bass playing has changed a lot. When I think of this style I think of that drum-rattling “Eight Miles High” intro. He plays with lot more motion on “Nowhere;” augmenting the wagon-wheel bounce. Written from Dylan’s domestic bliss in Woodstock with Sara, he articulated the 60s kids growing up and settling down; trading day-glo psychedelic clothes for earth tones: “Strap yourself to a tree with roots/You ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

When you think you’ve settled into a homier interpretation of the Byrds, I Am A Pilgrim smacks you in the face with boom! Fiddle! Are you ready for the country! ’Cause it’s time to go!

It’s banjo time, too! There’s double-bass and no drums! In the Byrds’ hands, “I Am A Pilgrm” is about more than Christianity. Though it is a traditional song about a pilgrimage, “I’m going down the river of Jordan/Just to bathe my wearisome soul/If I can just touch the hem of his garment, good Lord/Then I know He’d take me home,” it doesn’t alienate a listener from the outside. Chris didn’t like his voice on this, but I love his delivery. It’s tender and not in any way preachy. Simple, humble devotion. Anyone can relate to feeling like a pilgrim and a stranger. It’s human nature to make pilgrimages of some kind to some place to be part of something bigger than yourself. Take a rock-and-roll show; you go to feel transcendence and connection to the intangible.

Gram brought in a cover of the Louvin Brothers’ The Christian Life to record...and he originally sang it. WhenGram took flight from the Byrds, he was still represented by Lee Hazelwood; having never actually annulled his Submarine Band contract. But Chris’s partner Larry Spector also represented Gram. On top of that, he wasn’tactually signed to Columbia Records! He took a salary because he was rich as hell already and didn’t care about the money. These three things came back to bite the Byrds in the ass. According to Roger, Lee Hazlewood threatened to sue Columbia because Gram was still under contract to him. As not to get sued, Columbia told the Byrds to rerecord Gram’s vocals. Chris argued, “Roger’s voice was a major component of the Byrds’ sound. It’s possible the label wanted to hear more from the guy whose voice was strongly associated with the band rather than from a hired gun.” Whatever the reason, Roger re-cut “The Christian Life,” "You Don't Miss Your Water," and “One Hundred Years From Now,” and Gram was pissed-off about that ’til the day he died!

“Christian Life” was Gram’s “connection to a strain of terror and religiosity in traditional country. And as an expression of his dark humor and willingness to mess with people’s heads.” A playful nudge. Roger’s recordinggot totally lost in translation. Since he didn’t have that connection to fire-and-brimstone, his “Christian Life”sounds like he’s making fun of Christians; branding them dumb hicks for believing in god. A nudge at expense.Before doing my research, I thought this song was satire, but no! David Meyer is pretty shockingly anti-Roger as a whole in his book, but I have to agree on this one. Hearing Roger, who’d never sang this way on previous Byrds records, copy Gram’s accent makes me cringe. It’s like hearing Taylor Swift fake a southern drawl on her first two albums. Honey, you’re from Pennsylvania!

Every review of Sweetheart I’ve read seems to skip right over You Don’t Miss Your Water, but it’s key to understanding the album. There’s a pervasive theme in country music of loneliness. Achy breaky hearts, if you will. This opposed the “smile on your brother everybody get together right now” attitude of the late ’60s. This theme was lifted from the blues tradition. We even hear it now, turn on country radio and you can’t escape songs about guys drinking their sorrows away at the bar. “Water” and the next track lie in the tradition of the lonely barfly anthem; with downtrodden saloon piano and weepy steel guitar. Our narrator was blind to how much his lady loved him. He self-sabotaged and did her wrong. “I was a playboy, I could not be true.” He didn’t treat his old lady right and now she done left him all by his lonesome. “You don’t miss your water til your well runs dry,” he laments. You don’t know what you have until it’s gone. Lonesome songs like this might only have interjections of backing vocals, maybe some sorrowful “ooh”s. This is double-tracked almost the whole way through, and has those new-Byrdsy harmonies. In this way, “Water” contradicts itself.

Though his influence is felt, Gram properly enters the picture on You’re Still On My Mind; a Luke McDaniel cover. Aside from the Dylan covers, this is my most-listened song on Sweetheart. Of the stuff that made the cut for the record, it sounds the most like the songs I heard as a kid. The instrumental breaks trade piano, a combination of bar and boogie-woogie, and ever-present steel guitar. This is the most cymbal I’ve heard fromthe drums so far. Piano and bass trade off the role of the bassline.

Where “Water” was the brokenhearted man warming the bar seat, “You’re Still On My Mind” is the brokenhearted singer playing to the dance hall of lovey-dovey couples.

“A jukebox is playin’ a honky-tonk song,

‘One more,’ I keep sayin, ‘and then I’ll go home.’

What good will it do me? I know what I’ll find,

An empty bottle, a broken heart, and you’re still on my mind.”

While Gram wasn’t the strongest musician, he had a deep well of emotion to tap into. As put by Miss Pamela, “...even though he never spoke about his wealthy, weeping willow childhood, his grievous history had a hidden, unbidden hold on him.” Gram’s performance channels the feeling of being in a crowded room but still feeling lonely. When Gram’s voice works, it’s sweet and sad like honey-flavored bourbon. He wields a seductive tenderness; his inflections on “To try and forget you, I’ve turned to the wine,” and “So blue I could cry.” If the music wasn’t so lively, you might get teary. You just want to take his hat and hold him and there it is!! The fantasy of the lonely romantic! We’ve talked about that in respect to Tim Buckley in the past! Such is Gram Parsons’s hold on women in his lifetime, and honestly after.

The most overtly country, even bluegrass, cut is Pretty Boy Floyd; a Woody Guthrie song. It’s in line with another classic country trope: the righteous outlaw. The titular Pretty Boy is a Robin Hood-like character, feeding the needy on Christmas Day. I have to admit, this is so overtly country it even turns me off.

Gram’s two originals are back-to-back on Sweetheart, starting with Hickory Wind. It’s another classic tale of the country boy realizing, “Aw shucks, I never should’ve left my hometown for the big city. There’s no place like home.” It should be so cheesy, right? But every kid who's left their small town feels this at one point or another in life. I loved my bohemian art school life, I like where I am not. But once I get off exit 5, I just exhale. I don’t know I’m carrying the load until it’s lifted. The air is cleaner, the air traffic is zero, life is slower.

I’ve always been puzzled by the Byrds’ reliance on covers. Don’t get me wrong, they did a damn good cover. But some of their most memorable moments were originals like “Hickory Wind.” Its magical, breathless harmony vocals remind me of classic country backing vocals. I instantly thought of “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” The “moaning” Dobro is essential to scoring this track and others, Lloyd and JayDee are the unsung heroes of Sweetheart. A tasteful sprinkle of banjo by John Hartford acts more as an accent than a full line.

Of all of Sweetheart, One Hundred Years From Now feels most in line with the Byrds’ previous output. I think this lies in Chris’s bass playing; he got some of his rigidity back. At first, I thought this was the most “hippie” song on the album. Maybe I was swayed by the group vocals. But then I took a closer look: “Nobody knows what kinda trouble we’re in/Nobody seems to think it all might happen again.” This is a commentary on the hippie movement from the outside looking in. There is no preaching of utopia. Gram is saying “Hey, if we don’t check ourselves, a hundred years from now we’re still gonna be making the same mistakes.” And lookie here, 56 years on, we made, like, all the same mistakes. “Those who do not learn history” and so on.

Gene Autry sang Blue Canadian Rockies in the 1952 movie of the same name. It portrays yet another core trope to both country and rock-and-roll: missing your lady when you’re away. It’s not a standout moment onSweetheart, and neither is Gram’s rendition of Merle Haggard’s Life In Prison. I really wish “You Got A Reputation” and the Byrds’ recording of the International Submarine Band’s “Lazy Days” made the cut instead.It’s a prime example of the rock-to-country transition happening in real time. The latter is especially worthy, with its playful Chuck Berry-style guitars. Gram clearly thought the song worthy too. He recorded it twice in his lifetime. Had he lived to see his thirties, he probably would’ve recorded it a third.

Sweetheart is bookended by its Dylan covers, closing with Nothing Was Delivered. The song is apparentlyabout a drug deal gone wrong, but in that quintessentially Dylan way, it winds up as a prediction of how the last couple years of the 1960s would go. With the hippie dream, too, one Dylan never connected himself to, nothing was delivered. “Now you must provide some answers/For what you sell was not received.” There’s a karmic debt to be paid from the generation’s empty promises. Meyer says the song “closes as parody of the smarmy we-love-you-God-bless finish to every country concert: ‘Take care of yourself/And get plenty of rest.’” I see it more as the generational turn inward, from the collective back to the self, after the trauma the death of the hippie dream inflicted. Gram and Chris witnessed the final crushing blow to that dream; the Flying Burrito Bros. played the doomed Altamont Speedway show the next year.

The whole of Sweetheart works better than its parts. This album is the Byrds falling apart. After this, there would be just one Byrd; Gram took Chris with him to form the Burritos. It’s not their strongest album. So whywas I so interested in covering Sweetheart?

Country music is very much at the cultural forefront right now. Post Malone and Justin Timberlake have gonecountry...to little success. “Cottagecore” took over Tiktok, to much greater success. You can credit this to the pendulum swing to conservatism, but YouTube video essayists could tackle that topic better than a review of a 56-year-old album. But there’s subversion happening. Lil Nas X broke a Billboard charts record with his novelty song “Old Town Road.” Sabrina Carpenter put a Dolly feature on her album, then released “Manchild.” Chappell Roan channeled country on “The Giver.” Beyonce won Album of the Year for her Cowboy Carter LP; she made millions on its recently-concluded tour. And Taylor Swift said her rerecording of her self-titled album is complete. Like it or not, Taylor Fucking Swift’s return to country music will be one of the biggest music events of the decade.

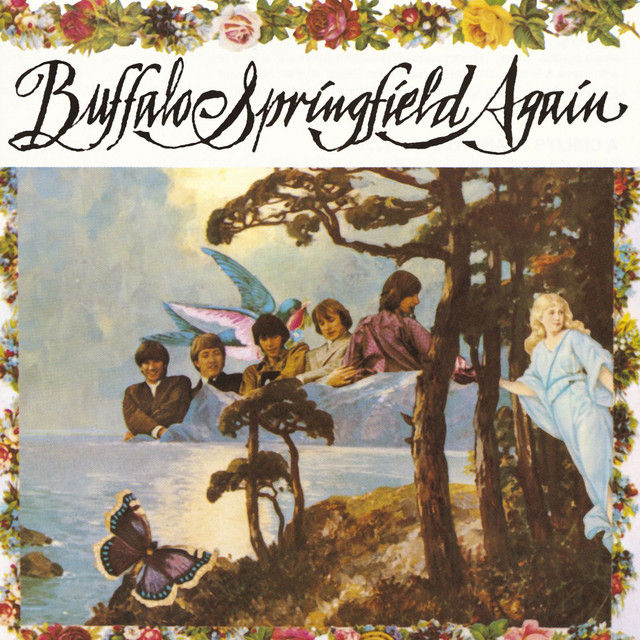

The exchange goes both ways; when I’m in the car with grandma, we can’t escape trap beats and autotune. Country once shunned these things for being “inauthentic” (their way of shunning "Black music.") The conversation between country and pop culture has been going for a long time. As evidenced by Robert Shelton’s New York Times quote from the beginning of this review, the Byrds weren’t the first to make that connection. Richie Furay’s “A Child’s Claim to Fame” off Buffalo Springfield Again might’ve been the first honest-to-goodness country rock to come out of Laurel Canyon. There’s always been a link between the two genres. Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly, and Elvis all grew up with country music. Dylan flouted the idea of collabing with Johnny Cash as early as 1965. But there was no lightning rod; no cosmic cowboy to fuse the two. Sweetheart took a hint of what I love in my adulthood, Laurel Canyon rock-and-roll, and placed it within a musical language I’ve known for a lot longer. Funny enough, this language was written in part by Sweetheart. It’s a real chicken-or-the-egg moment. Whichever it was, these deposed kings of the Sunset Strip got together with a Florida boy and blew the freakin’ lid off the whole thing.

Sure, Sweetheart of the Rodeo is important, but it says so in a language I can understand.

Personal favorites: “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “I Am A Pilgrim,” “You’re Still On My Mind,” “Hickory Wind,” “Nothing Was Delivered”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Des Barres, Pamela. I’m With The Band: Confessions of a Groupie. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2005.

Des Barres, Pamela. “Sweetheart of the Rodeo: Gram Parsons.” Please Kill Me, 8/30/2018. https://pleasekillme.com/gram-parsons/

Errigo, Angie. The Illustrated History of Rock Album Art. London: Octopus Books, 1979.

Hillman, Chris. Time Between: My Life As A Byrd, Burrito Brother, and Beyond. Chicago: BMG Books, 2020.

Hjort, Christopher, and Joe McMichael. So You Want To Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day, 1965-1973. London: Jawbone Press, 2008.

Meyer, David. Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music. London: Villard Books, 2008.

Proehl, Bob. 33 1/3: The Gilded Palace of Sin. New York: Bloomsbury, 2008.

Shelton, Robert. “A New Love Affair: Rock and Country.” New York Times, 12/10/1967. https://www.nytimes.com/1967/12/10/archives/a-new-love-affair-rock-and-country.html

“Cash Box Top 100 Albums.” Cash Box, 8/24/1968. https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/Cash-Box/60s/1968/CB-1968-08-24.pdf

I don't know what is happening. This was exactly album I was hoping you would cover. Appreciate all the early photos of GP, especially. I have been a Croz nut for decades and really never explored the Byrds or GP until the last few years. This country rock period is like quicksand. I can't get out.