Neil Young with Crazy Horse - Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

- Abigail Devoe

- Nov 3, 2025

- 18 min read

With Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, Neil Young re-introduced himself to us and introduced the world to Crazy Horse.

Neil Young: lead vocals, guitar, principle lyricist

Crazy Horse:

Danny Whitten: guitar, harmony vocals

Billy Talbot: bass

Ralph Molina: drums

Special guests: Robin Lane, vocals on “Round and Round (It Won’t Be Long);” Bobby Notkoff, violin on “Running Dry (Requiem For the Rockets)”

Produced by David Briggs with Neil Young

photographed by Frank Bez

“Young learned some lessons from his tumultuous time in the Springfield. He would never relinquish control over his music – or much of anything else in his life – again.”

quoted from: Jimmy McDonough, Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography (2002.)

The Horse

Upon leaving Buffalo Springfield (for real this time) in 1968, Neil Young made it clear to the music press he was no longer "the Hollywood Indian." He linked up with David Geffen’s protege and his friend Joni Mitchell’s manager, Elliot Roberts. He also met his new go-to producer, David Briggs.

Debut single “The Loner” flopped; and Neil’s self-titled album was promoted so poorly, no one was sure if it was even out! Reprise’s press release for Neil Young set up the classic “Neil” image: “...brewing, brooding, his stiff black hair dangling, making an ungainly Gothic arch across his forehead…” and “Challenging, absorbing, frustrating...about as much fun as Peer Gynt. And not sexy.” Damn. Unsurprisingly, this press release didn’t do much to move copies of the album!

Neil was never happy with his debut. The material was weak and it sounded bad to his ear. Around the same time as its release, Neil was hyping up a group called the Rockets.

Enter...The Rockets. That was anticlimactic.

Because Danny Whitten liked doo-wop and R&B while growing up in the Jim Crow south, he skipped out on the white dance halls in town; instead frequenting Black clubs. There, he learned how to dance. Discharged from the United States Navy because of his arthritis, he wound up in LA. His new go-to spot became the Peppermint West club (you may remember the original New York location for putting the twist on the map) and started dancing in competitions. There at the Peppermint, Danny met Billy Talbot. He wound up in Hollywood after a failed doo-wop group out in New York. They linked up with Ralph Molina and other friends to form Danny and the Memories.

It's weird seeing these guys so clean-cut and musically disciplined, but as Picasso said, "It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child."

Somewhere along the way, this doo-wop group wound up in San Fransisco dropping acid and became a rock-and-roll band; with a single produced by Sly Stone. Man, everyone is in this story! Danny started seeing Robin Lane, they collected fiddle player Bobby Notkoff, and Danny and the Memories became the Rockets. They had a couple close brushes with success: Danny Hutton tried to poach Danny for Three Dog Night, they ended up covering “Let Me Go” on their first album. The Rockets only released one self-titled album in March of 1968, intended for Atlantic but shunted over to White Whale because some a lyric in "Mr. Chips" (allegedly) offended exec Ahmet Ertegun. The band were ultimately more notorious for their jam sessions at Rocket HQ than for their music.

Mutual friend Autumn Amateau (likely) introduced bassist Billy Talbot to Neil. Neil was quickly absorbed into the Rockets’ jam sessions, which he moved to his place in Laurel Canyon. Neil took to Danny in particular. Nils Lofgren said,

“...Neil would be the first to tell you, that Danny was one of his early mentors and influences. Danny had that great deep ‘Bee Gees’ vibrato, with that California soul and lament.”

quoted from: Harvey Kubernik, “The creative energy behind Neil Young’s ‘Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere’” Goldmine, 10/12/2019.

When the Rockets landed a week-long residency at the legendary Whiskey a Go-Go in August of 1968, Neil inserted himself into it. This got him thinking he wanted the guys for his own backing band...but not all the guys. Neil looked to poach just Danny, Billy, and Ralph.

Neil returned to LA from Ann Arbor in January of 1969 and put the thing in drive. He booked initial sessions at a key location in the CrosbyStillsandNashiverse, Wally Heider’s studio, for what would become his re-debut: Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

The Songs

The original plan was to make a record structured like Neil’s live shows: one side of the LP would be Neil solo, the other with a band. Both “long songs” were never played in the same set, hence why they’re broken up across sides on the album. The oldest song on Everybody Knows is “Round and Round.” Originally written for the Springfield, Neil brought it to the Rockets as a three-part harmony piece. “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere” was attempted during Neil Young sessions five months before, but it just didn’t work.

But we can’t not talk about the fever.

“I had been sick with the flu, holed up in bed in the house. Susan (his wife) was bringing me soup and good stuff, but I still felt like shit. I was delirious half the time and had an odd metallic taste in my mouth.”

quoted from: Neil Young, Waging Heavy Peace (2011.)

The guitar closest to his bedside was left in D-modal tuning, producing the “Cinnamon Girl.”

“At the time, there was a song in E minor on the radio that I liked, ‘Sunny’ or something like that.” I can’t find what song he’s talking about, but he jammed on that and got “Down By The River.” “The song kept looping in my head, endlessly, like some things do when I’m sick and maybe a little delirious.” Last was the album’s longest track and dominant force, “Cowgirl In The Sand.” “This was pretty unique, to write three songs in one sitting, and I am pretty sure that my semi-delirious state had a lot to do with that.”

On the Archives, Neil wrote,

“I sure remember those sessions well. I still see Ralphie glance at me during the recording of ‘Down By The River’ or maybe ‘Running Dry,’ with a look of pure joy on his face. This was the beginning of something that really had it.”

quoted from: Neil Young, “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere” News: Neil Young Archives, 1/30/2019.

What was the atmosphere like in the studio? Stoned out of their minds! Naturally, a defining trait of this stuff was its length. “It just happened. We just started playin’ instrumentals and we didn’t stop. The energy was right. We just kept going.” Despite the tangents, Ralph described the album being recorded about as quickly as the band happened. “No rehearsals. Neil walks in with a song, then we jump in. We get it in one, two takes. After that, the feel, heart and emotion are lost. Any more takes, and now you're just playing a part. They were at Neil's house in Topanga. When you're young, there are no politics, nothing to get in the way. We just had fun playing – no thinking, just playing.”

Meanwhile, George Whitsell and the rest of the Rockets still had no idea Neil had basically exploded the band for himself. They naively thought the guys would cut this record, go out on tour, and that would be it. They were right about one thing: they did tour before Everybody Knows dropped. Recording was broken up between January and March of 1969 for tour, they went back out in May. Somewhere along the line, Neil suggested the name Crazy Horse. Neil Young with Crazy Horse, not “and.” “There was a distinction there. I am not sure why I did that, but I liked it being different. I liked that I was with them. Like we were together, not separate.”

George was wrong in thinking there’d ever be a Rockets again.

The Music

It’s no secret Crazy Horse is Neil’s favorite group he’s ever played with. A lot of people think the Horse are bad musicians, David Crosby included.

“The mere mention of Crazy Horse set David Crosby into a twenty-minute rant. ‘What does Crazy Horse give Neil Young? A clean slate. They should’ve never been allowed to be musicians at all. They should’ve been shot at birth. They can’t play. I’ve heard the bass player muff a change in a song seventeen times in a row. ‘Cinnamon Girl’ – he still doesn’t know it!’”

quoted from: Jimmy McDonough, Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography (2002.)

(Oh, Croz. You and your mouth are dearly missed!)

Neil has consistently defended the Horse, explaining they’re unpretentious, in-the-moment, fun, and real. All things a band should be in his mind. He stated Crazy Horse’s appeal perfectly to Nick Kent: “Well, I just liked these people. I wasn’t looking, I just found ’em.” In this way, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere was built in Crazy Horse’s image. They didn’t set out to capture a perfect moment. They wanted to capture The Moment. He said in 1970, “We were really feeling each other out, and we didn’t know each other, but we were turned on to what was happening. I wanted to record that, because that never gets recorded.” To my ear, Everybody Knowscaptures a certain naivete. To Jean-Charles Costa much later on, Neil said, “That whole album was like catching the group just as they were getting to know each other...we didn’t even know what we sounded like until we heard the album.”

What did they sound like? Earthy, a little gritty, naturalistic.

To my memory, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere was the first Neil Young album I cherished. I associate it with the tiny L-shaped apartment I lived at with six other people in my junior year of college. These were the Blonde on Blonde, stumbling through the front door with my cork wedges in my hand, lying on my back drunk listening to “Echoes” as the room spun around me years. Thin wild mercury, salt-of-the-rim. It was pretty grungy years, too. During the day, you would not find me without a green flannel and Doc Martens. It’s natural I’d have gravitated towards the godfather of grunge.

Where did Neil’s “godfather of grunge” epithet come from? Cinnamon Girl. Neil uses D-modal, AKA “grunge tuning;” where both E strings are tuned down to D. Neil and Steve Stills originally worked this out on “Bluebird,” figuring it sounded sort of like a raga drone. Very en vogue for 1967. Neil just never stopped using it: “Cinnamon Girl,” “Fuckin’ Up,” “Ragged Glory,” “War of Man,” “One Of These Days.” I could go on!

In his 30th anniversary retrospective for Rolling Stone, Greg Kot described the “Cinnamon Girl” riff as “elemental in its own way as anything on the first album by protopunks the Stooges (which came out the same year.)”

I don’t know about the Stooges comparison, but I know about the Egyptians.

Neil described the riff “like the Egyptians rolling giant stones up to a pyramid on logs. It’s huge and it’s moving. Unstoppable. Think Egyptians!” (If you didn’t read that in his inimitable voice in your head, you’re lesser for it.) It’s a stupidly simple ascend-descend, like the sides of a pyramid. The drums play a moronic stomp. The claps came from early sixties girl groups! Neil specifically cited the Angels' “My Boyfriend’s Back.” All of this was meant to undo the perceived damage Neil Young did. Flowery, overdubbed, and unfocused “Cinnamon Girl” is not. This song's rough-and-ready quality makes it at least one of Neil's three "flu songs" that earned him the epithet "Godfather of Grunge." Radiohead have played "Cinnamon Girl" live for years, Mudhoney interpolated Neil’s guitar sign-off for their song "Broken Hands." In a really weird intersection of my tastes, Hole interpolated "Cinnamon Girl" for "Starbelly" off Pretty On The Inside. (The album was produced by Kim Gordon, who toured with Neil while she was in Sonic Youth.) It's no surprise that Smashing Pumpkins covered "Cinnamon Girl" as well; it appears as a bonus track on new reissues of their Pisces Iscariot compilation.

In how loose our vocalists’ delivery is, Danny’s harmony sounds remarkably close to Neil’s lead and tight. For a long time, I assumed it was Neil double-tracked!

“I wanna live with a cinnamon girl,

I could be happy the rest of my life with a cinnamon girl.

A dreamer of pictures, I run in the night,

You see us together, chasing the moonlight, my cinnamon girl.”

“Cinnamon Girl” is rumored to be about Jim Morrison’s old lady, Pamela Courson – “cinnamon” referring to her red hair. A much more plausible identity of Neil’s muse at this time is folk singer Jean Ray. Notably not Neil’s wife!! He married Susan Acevedo shortly after leaving the Springfield (it seems he’s got a thing for waitresses, they met at the diner Neil was a regular at.) By the dawn of the new decade, the marriage was already on the rocks.

“Cinnamon Girl” is a picture of romance in Laurel Canyon. Striking just the right balance between committal and non-committal, domestic and freewheeling. Neil was right to change the lyric from “I want to marry a cinnamon girl,” it would’ve been out-of-step with the times...and slightly bigamous.

“Ten silver saxes, a bass with a bow,

The drummer relaxes and waits between shows for his cinnamon girl.”

Our cinnamon girl is a groupie, always waiting with praise and open arms. The looseness of Crazy Horse plays into this smoky backstage setting, but the melody of the bridge makes it more wired than laid-back. I love the scoop up those rock-solid guitars make turning out of the last line of each verse; rolling the log up the pyramid with a great thrust. Our narrator’s point of view switches to either that drummer in this struggling band or our cinnamon girl herself, needing help from her folks to keep chasing the moonlight. “Pa, send me money now, I’m gonna make it somehow/I need another chance.”

This is followed one of Neil’s signature one-note solos – more on that later – and the least enthusiastic “woo” I have ever heard. It ends with a fadeout of perfect length, and a muscular, ambiguous, and all-too-brief Neil solo of more than one note.

“Cinnamon Girl” is a song so indisputably solid, so good, it makes a girl want to dye her hair red.

At surface level, the title track is a basic story of, “simple country boy regrets leaving his small town for the big city.” “I think I’d like to go back home and take it easy,” “I wish that I could be there right now.” This country cliché masks how Neil feels about the Laurel Canyon scene. “Everybody seems to wonder what it’s like down here/Gotta get away from this day-to-day running around/Everybody knows this is nowhere.” The optimism and magic that once watered the flora in the Canyon is drying up, according to Neil. He had a point. By 1969, three years into the first wave of Canyon pop, the hippies were getting rich and moving out of the Canyon. Take John and Michelle Phillips, for instance: they bought a house in Bel Air and drove fancy cars.

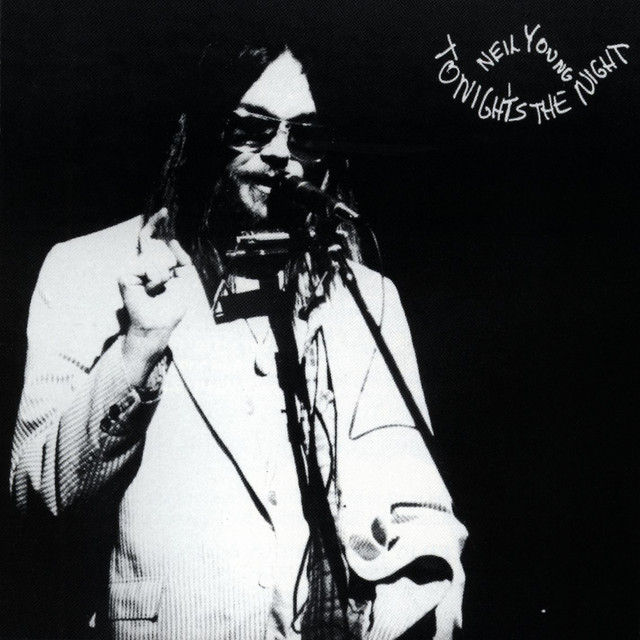

It’s interesting to note Harvest opens with “Out On The Weekend,” “Think I’ll pack it in, buy a pick-up, take it down to LA.” Then on Tonight’s The Night, he’s got a whole song about renting a car and escaping to a diner in Albuquerque where no one knows who he is. I’m sure he repeated the cycle a few times between these albums, but the example stands. One of the recurring themes of Neil’s writing is, "Do I stay or do I go? Do I go now or go later?" Exactly what you run from is what you end up chasing.

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere is permeated by the signature Crazy Horse drum beat. Boom-boom-thak. Boom-boom-thak. Boom-boom-thak.

I’ve heard it so much, it’s haunting my dreams.

The standout player of “Everybody Knows” is Danny. His playing and Neil’s click together so seamlessly, you miss the intricacy on the first few hundred passes. It comes naturally. That’s the power of musicians in the moment. And you know a harmony is damn good when you sing it instead of the melody. I also love the goofy “la la laaa”s, stoic Neil won’t take himself too seriously.

Cameron Crowe included this song in Almost Famous; "Everybody Knows" plays over the high school kids' party in Oklahoma or wherever that Russell Hammond and Will Miller crash. "I AM A GOLDEN GOD!" and all. I found it an interesting choice interesting to play this, the title track from an album released in 1969, over a scene of a party in 1973. It shows that a., this album stuck like glue in its time, and b., rural towns are usually a few years behind the culture of cities.

Denny Bruce said, “Danny Whitten, in the Crazy Horse sound equation, was the heart and the soul.” He plays the second in a gorgeous twin acoustic guitar part on Round and Round (It Won’t Be Long.) It’s unclear who sings that third part on the choruses; some texts imply it’s Danny on a super-high falsetto, to my ear it sounds like overdubs by guest vocalist Robin Lane. One of the most consistently underrated songs of Neil’s classic period, “Round and Round” is about the ups and downs of a relationship that has run its course. Neither party is willing to leave: for pride, fear of the new, or whatever else. “How slow and slow and slow it goes/To mend the tear that always shows.” The disconnect festers, getting worse through complacency. They’re lying to themselves. I love how the music follows the “round-and-round” of the lyrics. Robin’s wordless vocals over Neil’s verses are high like a swing on a carnival ride; made remarkable as she thought the final take was just a run-through. Neil’s vibrato is really wide on the end of, “To shelter your pride and you cry.” Singing live was a struggle for him at this time. One can imagine him hunched over his guitar, rendering himself totally out of breath.

About Down By The River, Neil said in 1970,

“There’s no real murder in it. It’s about blowin’ your thing with a chick.”

quoted from: Peter Doggett, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (2024 ed.)

Very funny, Neil.

If you think about it, the root of that situation isn’t too far off from what actually happens in the song: a man unable to control himself. One might call “Down By The River” the worst possible outcome of toxic masculinity. (I know, I know. Buzzword so overused it’s practically meaningless now. But hang in there.) Jealousy and entitlement has driven our narrator to do something he can’t take back: shooting his baby dead down by the river. Her killing is him exacting control in the highest degree: if I can’t have you, no one can.

At least in a song like “Hey Joe,” there’s a clear motive: the woman stepping out. The guy in “Down By The River” is even more terrifying because we’ve got no motive. The closest thing we have are the opening lines:

“Be on my side, I’ll be on your side,

There is no reason for you to hide.

It’s so hard for me staying here all alone

When you could be taking me for a ride.”

This implies he tried guilting her into being with him, then killed her because she turned him down. Fucking dark.

The writing of “Down By The River” reveals a scattered frame of mind – induced by murder or fever. An oddball line like, “This much madness is too much sorrow/It’s impossible to make it today” only add to intrigue. Everything about this song is heavy. The fuzzy surface noise in the beginning hangs like thick, hot fog over the river bed. Billy’s unrelenting bass line repeats so many times, it’s mind-numbing. It doesn’t feel like notes anymore, it feels like inevitability. The group vocals over our narrator’s confession chorus feel like other spirits, as do lazy, atmospheric guitar slashes and whirs. The guitar tone ranges from sharp to vague as this nine-minute exercise builds into a Neil and Danny pick-guard knife attack.

I’m not above clowning on Neil’s one-note things. I know it’s an exercise in tension and all, but “Down By The River” is something else. The best-worst guitar solo ever. It sounds like Neil’s fingers are glued to the fretboard! This mental image is made even funnier by his stacatto moving around ever so slightly. He’s trying so hard to free himself! Is this song “too long?” That’s hard to say. If you’re like me and take “Down By The River” as the psyche of the guy who lost control of his impulses in the worst way...it’s only a little long.

Everybody Knows is a frontloaded record for sure. Though I love the side two opener The Losing End (When You’re On) and advocate for Running Dry (Requiem For The Rockets,) they’re no “Cinnamon Girl,” “Everybody Knows,” and “Round and Round.” “The Losing End” is a simple country bounce about a guy left lonesome after his lady splits town. Another case of Danny singing a harmony so good it renders the melody obsolete, and some more of the guys goofing off. (In his best Mickey Mouse impression, “Hit it, buster!”) “Running Dry” is heavily indebted to classic folk songs; repetitive so they’re easily sung by a crowd. I advocate for “Running Dry” purely for Bobby Notkoff’s violin playing. I wouldn’t be surprised if a 1975 Bob Dylan picked up a copy of Everybody Knows and fixated on “Running Dry.” Having Scarlet Rivera on the Rolling Thunder Revue and Desire was in shades of “Running Dry.” I’m also taken aback by how lo-fi Neil’s lead vocal is on the verses versus the choruses and his own harmonies. Was this recorded at two different studios?

Closing out Everybody Knows is the longest song on the album: the ten-minute blockbuster Cowgirl In The Sand.

“Old enough now to change your name,

When so many love you, is is the same?

It’s the woman in you that makes you want to play this game.”

The chorus of this song is controversial. Or, at least, it should be.

Some critics, authors, even the Wikipedia page for “Cowgirl” say this is about a promiscuous woman. Other critics paint it misogynistic. I don’t think “Cowgirl” is that simple.

Not to bring Crosby, Stills, and Nash into this, but I’ve always interpreted “Cowgirl” as a “You Don’t Have To Cry” situation; a woman grappling with fame. No “managers and where you have to be at noon” (struggling to pace her public and private lives) here. Our Cowgirl struggles with “the game.” Gaining validation from fan adoration, while being lonely in her personal life; and the weird minefield that is parasocial relationships. Being in the spotlight will inevitably garner those. Divorcing yourself from that subconscious can take a lifetime. These people think they know you, these people think they love you, but it’s not really “you.” It’s an image you sell off looks or personality or whatever. “When so many love you, is it the same?” No. Our subject being a woman adds a layer of complexity. Society teaches women to tear each other down for the approval of some man, even if that’s not what your head or heart really want. We’re taught it's the ultimate goal.

The genius of “Cowgirl” is that Neil is one of these guys exalting an image of her they’ve made up in their heads. “Hello woman of my dreams, is this not the way it seems?” Even the opening lines, “Hello cowgirl in the sand, is this place at your command/Can I stay here for a while?/Can I see your sweet, sweet smile?” invoke a guy going to a show or the movies to admire her from afar. What “Cowgirl” and “You Don’t Have To Cry” have in common is that the man (our narrator) is commenting on the woman's cognitive dissonance from the outside.

This feels like the sharpest music on the album since “Cinnamon Girl.” The band is with it. Ralph is switching up his playing for once! Billy does in fact flub his change like seventeen times (not really,) but I appreciate him being flexible with his typically droning part to compliment what the rest of the guys are doing. The music rolls like tires down the freeway. Neil’s offbeat, unpredictable phrasing and distortion keep this caddy from getting stuck in the sand.

In interview for Mojo, Nick Kent asked, “...you had this image of someone very confused, isolated, emotionally fragile and introspective. Was that a fair evaluation of your condition?” Neil responded with, “No, not really, I didn't see myself like that, I always thought there was a funny side to my music.” When asked, “Were you concerned about this image?” Neil replied, “What image? Listen, there was nothing to be concerned about. I really just wanted to make music...My only concern was to make the fuckin' records sound right.” (Sounds about like audiophile Neil.) An image is,

“...like a mirror. And you can't get away from a mirror if you stand in front of it all the time, right. But if you step away from it, you don't notice it any more. And that's what the stage is like for me. See, an image becomes meaningless in as much as it's always temporary.”

quoted from: Nick Kent, “‘I Build Something Up, I Tear It Right Down’: Neil Young at 50” Mojo, 12/1995.

That right there is the core of Neil. An image is meaningless in as much as it’s always temporary.

Neil said the difference between his self-titled debut and Everybody Knows was playing with people. Greg Kot agreed. “If Neil Younghad an aura of careful subtlety bordering on tentativeness, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere felt raw, rushed, energized.” Neil didn’t find an audience with this album – that wasn’t until After The Gold Rush and the massive commercial success of Harvest. What he did find were musicians who truly spoke his musical language, acted on the same instincts, and didn’t play to bullshit. They sought feel over all else.

Everybody Knows is our first clear portrait of Neil. Dylan, the Stones, the encroaching influence of country music coming up through the Canyon. And apparently Roy Orbison! In the liner notes of the Decade compilation, Neil wrote, “I remember Crazy Horse like Roy Orbison remembers ‘Leah’ and ‘Blue Bayou.’”

The intrigue of Neil is that we’re always hearing from a different facet of him. Even if I don’t like everything he’s done, it never bores me. He’s never static. In the pop culture consciousness, the Neil of Everybody Knowsstill stands as “Neil Prime.” A thin, reedy voice, sometimes whimpering. Guitar work straddling between hero and noisy kid with an amp. Unexpectedly catchy tunes with lyrics that invoke what is deep and known, but not always easily acknowledged and rarely articulated. Suede and flannel. With Crazy Horse. So simple it makes you go “duh!” But he was somehow the guy to crack the code. Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere is our second-first introduction to Neil. Not too shabby for a do-over.

Personal favorites: what the hell, I'm feeling generous. The whole thing.

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Doggett, Peter. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. New York: Atria, 2024 ed.

Einarson, John, with Richie Furay. For What It’s Worth: The Story of Buffalo Springfield, Updated Version. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2004.

Kent, Nick. “‘I Build Something Up, I Tear It Right Down’: Neil Young at 50.” Mojo, 12/1995. https://thrasherswheat.org/tfa/mojointerview1295pt2.htm

Kot, Greg. “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.” Rolling Stone, 8/19/1999. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/everybody-knows-this-is-nowhere-99581/

Kubernik, Harvey. “The creative energy behind Neil Young’s ‘Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.’” Goldmine, 10/12/2019. https://www.goldminemag.com/articles/the-creative-energy-behind-neil-youngs-everybody-knows-this-is-nowhere/

McDonough, Jimmy. Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography. New York: Random House, 2002.

Wisniewski, John, and Jason Gross. “Ralph Molina/Crazy Horse.” Perfect Sound Forever, 2/2021. https://www.furious.com/perfect/ralphmolina.html

Young, Neil. “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.” News: Neil Young Archives, 1/30/2019. https://neilyoungarchives.com/news/9/article?id=Album-Of-The-Week-Everybody-Knows-This-Is-Nowhere

Young, Neil. Waging Heavy Peace. New York: Penguin, 2012.

neil seemed to be walking on shifting sands in his musical relationships to this point so to find true band mates must have been satisfying. i admire the sound they create on the album, creaky structures and all, but the csn link up with the mistrust, the jostling for space, produced the greater album imo. go figure.

i'm interested in your reading of the lyrics AD. it probably reveals more pontentialies of meaning. i think at a certain time of day though, with the light falling on the objects in a room in a certain way, it isn't wrong to see the lyrics as mean, misogynist, as well as dark in tone, in the way you've stated.

the student experiencing…