Bob Dylan - Highway 61, Revisited, 60 Years Later

- Abigail Devoe

- Sep 1, 2025

- 26 min read

“Exit the ‘Woody Guthrie jukebox,’ enter Rimbaud with a Rickenbacker.” With Highway 61, Revisited, Bob Dylan kicked the door in on what pop music could do.

Bob Dylan: vocals, guitar, piano, harmonica, fire whistle

Mike Bloomfield: guitar

Paul Griffin, Frank Owens: piano

Al Kooper: organ

Harvey Goldstein: bass

Russ Savakus: bass, double bass on Desolation Row

Bobby Gregg: drums

Bruce Langhorne: tambourine

Special guests: Charlie McCoy, guitar on “Desolation Row;” Joe Macho Jr., bass on “Like A Rolling Stone;”Tom Wilson, producer of “Like A Rolling Stone

Produced by Bob Johnston

photographed by Daniel Kramer

“One day he was a respected young songwriter, the next he was this thing. The Voice of A Generation. The Man With All The Answers. People were at him all the time. Tell me what to think. Tell me where to stand. Tell me who to be. It was relentless. You or I couldn’t have stood that kind of pressure…”

quoted from: Mark Polizzotti, 33 1/3: Highway 61 Revisited (2006.)

Though his accounts have changed many times over sixty years – Dylan’s never been the most reliable in interview – his stories retain the spontaneity of writing his greatest hit.

The lyrics written either on the plane home from his spring 1965 UK tour, immortalized in Don’t Look Back, or at his place in Woodstock, depending on who and when you ask. To Robert Shelton, Bob said the early draft “was very vomitific in its structure. It seemed like twenty pages, but it was really six. You know how you get sometimes.”

God Said To Abraham

While recording a slimmed-down “vomitific” work, three big things happened that would shape what would become Highway 61, Revisited. Firstly, Bob invited blues guitarist Mike Bloomfield to record. Mike’s first impression...wasn’t great.

“I thought it was just terrible music. I couldn’t believe this guy was so well touted. I wanted to meet him, cut him, get up there and blow him off the stage.”

quoted from: Mark Polizzotti, 33 1/3: Highway 61 Revisited (2006.)

Clearly their meeting went a little differently than Mike expected! Dylan had decent enough blues chops; back in England, he’d jammed with John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers featuring Eric Clapton.

The June 15th sessions didn’t work out (“Like A Rolling Stone” just wasn’t meant to be in waltz time,) so everyone was called back the next day. Mike blew into Columbia Studios from the pouring rain on the morning of June 16th with his guitar and without a case.

Who saw him stumble in without his guitar case? Organ player Al Kooper...who wasn’t actually an organ player! He was simply a guest of producer Tom Wilson.

Al recalled, “In 1965, being invited to a Bob Dylan session was like getting backstage passes to the fourth day of creation.” Al thought he could play a little guitar, but then Mike showed up. From there out, it was very clear who the guitarist in the room was! Original organ player Paul Griffin was moved to piano after a few takes, leaving the organ open. Then, Tom got a phone call and had to leave the control room. In a split-second, Al made one of the most decisive moves in rock-and-roll history; one that would change his life path forever. He snuck into a Bob Dylan recording session to play an instrument he could not play.

About that session, Al said to Rolling Stone it was “totally punk. It just happened.” This corner of music commentary very much appreciates the punk ethos; Al’s steel-balls move certainly falls into that category. Though he was “fumbling (his) way through the changes like a little kid fumbling in the dark for a lightswitch,” it was somehow good enough for Bob!

“Like A Rolling Stone” was Bob’s last session with Tom Wilson. The stories are vague on both sides, but point to a blowup between the two regarding “Like A Rolling Stone.”According to Clinton Heylin, in a classically Dylan move, he sarcastically requested Phil Spector oversee the next session. Terry Melcher was briefly considered (the guy who produced the Byrds producing Bob, could you imagine that?) but he was outbid by Bob Johnston.

“Like A Rolling Stone” was released on July 24th, 1965, with “Gates of Eden” on the B-side. At a total run time of eleven minutes and 48 seconds, this would’ve been the longest seven-inch, 45 RPM single in rock-and-roll history to date. Columbia nearly rejected it for being “too long,” but this is Bob Fucking Dylan in the 1960s, and you don’t say no to your golden boy!

“Rolling Stone”’s on rock-and-roll history cannot be overstated. It’d be pointless to waste space on this web page listing every single notable critic’s tribute to rock-and-roll’s skeleton key song. Hell, Greil Marcus wrote an entire book about it! Besides, our tank-top-wearing hero from last week said it better than those guys ever could.

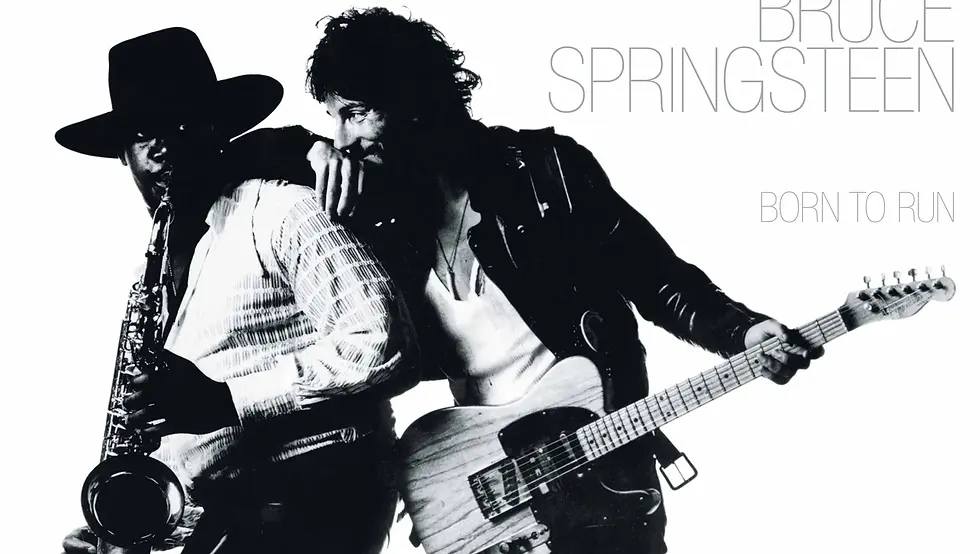

“The first time that I heard Bob Dylan, I was in the car with my mother, and I think we were maybe listening to WMCA. And on came that snare shot that sounded like somebody kicked open the door to your mind...”

quoted from: Bruce, Springsteen, “Induction Speech for Bob Dylan.” (Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, New York, NY, 1/20/1988.)

Think about what else was on the radio at the time. Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe.” The Beach Boys, “California Girls.” “Unchained Melody.” Not to mention a shit ton of Dylan covers! The Byrds had their first big hit with their “Mr. Tambourine Man” in June. The Turtles recorded “It Ain’t Me Babe,” and Cher covered “All I Really Wanna Do.” (Apologies, queen, but no one can top Bob’s wine-drunk performance.) “Rolling Stone”peaked at number two the week of September 4th; only kept off the top by the Beatles. Dylan saw the Fab Four occupying the entire Billboard top five the week of August 4th, 1964, with seven more songs in the rest of the Hot 100, and replicated it to the best of his ability. As expertly put by author Mark Polizzotti, “Exit the ‘Woody Guthrie jukebox,’ enter Rimbaud with a Rickenbacker.”

The day after “Like A Rolling Stone” kicked the door in, Rimbaud with a Rickenbacker made his debut.

The Titanic Sails At Dawn

There’s one big thing cleaving Highway 61’s timeline in half, and it’s shaped a lot like the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

That’s because it’s the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

Whole books have been written about this one weekend. One of those books was adapted into a movie starring Timothee Chalamet – which I saw opening weekend, dressed as Bob Dylan!

What we can all agree on in sixty years of hindsight is that there was a Newport Folk before 1965, and a Newport Folk after 1965.

Before, it was a Folk Festival. We hardly hear about the Friday and Saturday workshops anymore; dominated by traditionalists. Sunday was the “new folks” day. No matter who you were, Texas Prison Work Song group or the voice of a generation, it was a gateway festival. Joe Boyd phrased Newport’s appeal best: “Invitations represented an opportunity to appear before thousands of the most aware and influential kids in America, to say nothing of the worldwide media. Like knighthoods, they were seldom turned down.”

The Saturday night concert was the only opportunity Newport’s young demographic had to see someone who looked and talked like them, singing about topics relevant to them. That’s not to say the young crowd was disinterested in social issues of the day, quite the opposite. It manifested in a different way. The winds were changing. The 1965 Newport songwriters’ workshop was the first not to bear predominantly topical material. Folk songwriting had begun to turn inward.

A healthy dose of fate went into Dylan’s set. Poor scheduling had his set sandwiched between old-school acts; like Cousin Emmy and the Fiddler Beers Family, with Peter, Paul and Mary. This resulted in a very mixed crowd; of people who went to see everyone but Dylan and people who went for the express purpose of seeing Dylan. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Elektra’s first rock group, were set to play but got rained out. Mimi and Richard Farina requested a backing band, but it didn’t pan out. Had Bob not done what he did, their set would’ve been the defining moment of the festival! Everyone forgets about them. And Phil Ochs! The one detail that challenged the narrative of the whole of 1965 Newport Folk for me was that Phil Ochs, one of the folkiest folkies to folkie at this time, was not invited to play that year of the festival. So the idea Dylan plugged into an entirely unplugged world is false. However, it does seem he showed up looking for a fight! He didn’t bring an acoustic guitar with him to the grounds on Sunday night; he had to borrow one from either Peter Yarrow or Johnny Cash. But the fight began before he stepped on stage. In a sea of American workwear (think double denim,) Dylan showed up sporting the London look. The green polka dot shirt he wore to sound check was such an important symbol of the weekend, costume designer Arianne Phillips insisted upon Timothee sporting one in A Complete Unknown.

On the day of, Bob wore a black leather jacket, a salmon shirt, “peg leg” black pants, and the Cuban heels that would become synonymous with him. Elijah Wald said Bob’s positively Carnaby Street getup “(drew) to himself the whole shebang of the teenage rock and roll revelers whose screams and squeals of ecstasy as the performer came on stage were all too obnoxiously apparent.”

The physical fight over Dylan’s set, though, is a myth; it came from Alan Lomax and Al Grossman getting into it over one slighting the other’s act. Pete Seeger and the axe is also a myth. This came from him participating in a work song demonstration earlier in the day.

Bob wasn’t Newport’s first electric set, but he was certainly their loudest. This was 1965, and not exactly the crowd to be experiencing Vox Beatle amps in person! Was there cheering? Were there hecklers? Was it a mix of both? Did he stun Newport into silence? Even the film footage itself is unreliable. It’s been edited to hell over the years! The story you’ll get depends on who the storyteller is and where they were on the festival grounds.

“...there were upward of seventeen thousand people in the audience, with every seat and space on Festival Field filled and another two to four thousand listening from the parking lot. What anyone experienced depended not only on what they thought about Dylan, folk music, rock ’n’ roll, celebrity, selling out, tradition, or purity, but on where they happened to be sitting and who happened to be near them…”

quoted from: Elijah Wald, Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and The Night That Split the Sixties (2015.)

The broad generalization of this night – which I generally agree with – is that Dylan’s set drew the line in the sand between oldheads who believed folk music was by the people and for the people, and the new kids on the block, who used the folk music format to articulate their own concerns.

In any way, Newport Folk was the live debut of “Like A Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer.” Bob wrote the rest of what would become Highway 61, Revisited at his new place just outside of Woodstock, New York. So was the beginning of another major chapter in Dylan history – and such is the principle that there are rarely defined “beginnings” or “endings” in said history.

Bob and his studio group returned to Columbia six weeks after “Rolling Stone” sessions; presumably riding high on the single’s success. “Tombstone Blues,” “Phantom Engineer,” now reworked into “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry,” and follow-up single “Positively Fourth Street” were all recorded on July 29th, 1965.“From A Buick 6” came the next day, July 30th. August 2nd bore final takes of “Ballad of a Thin Man,” “Queen Jane Approximately,” the title track, and “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.” “Desolation Row” began its journeyas an electric song on the July 29th session, but was rerecorded at the last minute on August 4th as an acoustic number.

How Does It Feel?

Every rock critic worth their salt has said something about this album. Not only that, but it’s been out for sixty years! Since I had the misfortune of being so late to the party, I have sixty years of commentary to measure up to. Literally anything I say will feel redundant! All I, or any of the critics past a certain point have, are our individual experiences with Bob Dylan’s material.

When people ask me who my first love was, I say Bob Dylan. When I first discovered his music at age 19, it flipped the switch of my consciousness. Not once in my life have I felt comfortable or at peace. There are so many facets of myself coexisting. I can’t possibly be content expressing just one. I must wear costumes. It’s in my nature. I have to change. “I contain multitudes.” It’s why I love Neil Young now that I’m older and why I loved Bob when I was young. I thought I was the last of a lost civilization until I encountered his work. For the first time in my life, I heard someone else speak my language.

I started listening to Bob through the Manchester Free Trade Hall bootleg – the “JUDAS!” show. The themes,the sound, the set list, band, its perfect hybrid between Highway 61 and Blonde On Blonde, and that entry point are crucial to how I perceive the rest of Bob’s work. As is how I first heard Manchester Free Trade, with Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 soon after: on a road trip that changed my life.

Let’s indulge in something I do not do enough of on this series: album title analysis. Highway 61, Revisited. From the man himself:

“Highway 61, the main thoroughfare of the country blues, begins about where I began. I always felt like I'd started on it, always had been on it and could go anywhere, even down in to the deep Delta country. It was the same road, full of the same contradictions, the same one-horse towns, the same spiritual ancestors…It was my place in the universe, always felt like it was in my blood."

quoted from: Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One (2004)

Dylan said Highway 61 felt like home because it kinda was. It passes through his hometown of Duluth, Minnesota. Revisited, though, is a little trickier. Bob had to fight Columbia to get “Revisited” in the title.

Just as Al Kooper described recording “Like A Rolling Stone” as “totally punk,” Joe Boyd and Mark Polizzottialso make punk references in their texts. One of the core tenets of Bob Dylan is pissing people off. See Newport Folk, Self Portrait, saying the N-word with a hard R in “Hurricane.” Even his Victoria’s Secret commercial! Seriously, what in the world was that?! This was the kid voted most likely to join Little Richard’s backing bandin his high school yearbook. He brought a Strat, the kind of guitar Buddy Holly played, to Newport. “Revisited” is essential to the thesis of the album. Dylan insisted in interview this was not a musical departure, not a deliberate middle-finger to the folkies, but a return to where he came from.

Author Mark Polizzotti clarifies, “What Dylan has abandoned in Highway 61, Revisited is not his sense of outrage or protest, but the illusion of community.” Joe Boyd elaborated further in his book, White Bicycles:“Like the Acmeist poets of Russia in the ’20s, he confused and frightened commissars with his opacity. He was no longer outer-directed.” (“Outer-directed” meaning topical songs; which point outrage at a specific entity.) ’65 Dylan onward is so difficult to pin down because he, she, we, they, you, I, are rarely static in his songs. This, of course, comes from what he was reading at the time. Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Blake, Rimbaud. He was writing his own book, Tarantula, though he just kept kicking that can down the street!

The secret ingredients of Highway 61’s music were Bob Johnston, Al Kooper, and Mike Bloomfield. Highway,Blonde On Blonde, John Wesley Harding, and Nashville Skyline were all produced by Johnston. (Self Portrait too, I guess. It’s not as bad as you all think it is! But it’s definitely not his best!) Johnston did wonderful work outside of Bob, shoutout to Songs of Love and Hate. Johnston was only producer who could capture “thin wild mercury.” What made thin wild mercury? Al Kooper’s playing; which alchemized any given song’s whole arrangement into the mid-’60s Dylan magic. But “thin wild mercury” couldn’t exist with Mike Bloomfield around. It’s what makes Highway 61 unique amongst Bob’s mid-’60’s output. Mike’s playing is simply too hopped-up to fit any descriptor of “thin.” Wild, sure.

Like A Rolling Stone could be a whole Vinyl Monday in and of itself. It’s already taken up most of this review!

It’s so difficult to explain “Like A Rolling Stone” because it feels so fundamental to me. Like, how do you verbally explain to someone how to walk? Its title could be a reference to Muddy Waters’ “Rollin’ Stone,” just as likely is Hank Williams’ “Lost Highway.” One loops into the highway theme, both fit “revisited.”

“Once upon a time, you dressed so fine,

Threw the bums a dime in your prime,

Didn’t you?

People call, say ‘Beware doll,

You’re bound to fall,’ you thought they were all

Kidding you!”

Bob has described the lyrics as “a rhythm thing on paper all about my steady hatred, directed at some point that was honest.” So, who is this song about anyway? Is it Andy Warhol and/or Edie Sedgwick? A “chrome horse” certainly sounds like a Factory creation. But no, Dylan didn’t make contact with that crowd until the fall of 1965. It would certainly be compelling if “Rolling Stone” were directed towards Marianne Faithfull. It’d bequite the self-fulfilling prophecy, but I haven’t found concrete evidence. Bob had little sympathy for poor little rich girls and boys of the world. Ironic, considering he himself grew up middle-class and relatively comfy. Bob’s treatment of this spoiled subject is mean as hell; meaner on the page than on the recording. It’s a little cruelty, a little compassion, and the delivery is just the right dosage of manic joy. Bob takes glee in this person learning independence the hard way; having to make shit deals like the rest of us.

“You say you never compromise

With the mystery tramp, but now you realize

He’s not selling any alibis,

As you stare into the vaccum of his eyes,

And say, ‘Do you want to

Make a deal?’”

A gritty, sleazy Faustian bargain. Bob delights in seeing someone who pushed others down to get ahead tripping and falling themselves. But don’t we all do that to get ahead? Didn’t Dylan himself do that to, oh I don’t know, Joan Baez?

A delightfully condescending “Aaaaaw!” Begins,

“Princess on the steeple

And all the pretty people, they’re all drinkin’, thinkin’ that they’ve

Got it made.

Exchangin’ all precious gifts,

You better take your diamond ring,

You better pawn it, babe!”

The best line delivery on the whole of Highway 61 is that, “You better pawn it, babe!” It sounds like he’s got a big fat smile on his face and two middle fingers in the air.

If I must say who or what “Like A Rolling Stone” is about: it’s partly Bob’s response to the hordes of people hailing him as The Voice of A Generation, asking him where to stand and who to be. He takes this space to criticize people who did everything they were told by parents, peers, partners, and society, and are unhappy because of it. If you followed all the rules and wound up with a miserable life looking for external validation, it’s your own fault, dummy. (How very Zappa of you, Dyl.) The greater thesis of “Rolling Stone,” though, is this: there’s nothing more freeing than being a nobody. “When you’ve got nothing left, you’ve got nothing to lose”echoes “Been down so long it looks like up from here.” There you go, some Richard Farina for you.

The following chorus has spawned the titles of countless biographies and biopics:

“How does it feel?

To be out there on your own,

With no direction home?

A complete unknown,

Like a rolling stone”

Bob gets to wailing it like a man possessed by the specter of himself we perceive him as. From Greil Marcus’s epic piece on this song:

“‘How does it feel’ doesn't come out of his mouth; each word explodes in it. And here you understand what Dylan meant when he said…‘I had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, How does it feel?’ Dylan may sing the verses; the chorus sings him.”

quoted from: Greil Marcus, Like A Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (2005.)

As for the music? Ramshackle perfection. It sets a bright scene for Dylan to deliver his “vomitorious” and spiteful, but joyful masterpiece. Mike was kept on a tight leash (“none of that B.B. King shit,”) but he adds musical commas into Dylan’s ramble. Al’s organ is screaming over top. Dylan breathlessly wheezes into his harmonica, and the tambourine places this song firmly in the mid-’60s. Paul Griffin on piano gives the arrangement its color; equally dramatic and playful. Bobby Gregg gets the credit for the iconic “crack” snare-shot, but I love his thunderous returns to the verses just as much. This is one tight group. Listen to how they rise in anticipation through the prechorus before Bob returns to his middle-finger-to-the-air, “How does it feel!”

It was a superb choice to follow “Like A Rolling Stone” with Tombstone Blues. Bob Johnston said Dylan was in charge of sequencing. He builds building the world of Highway 61 with his sheer onslaught of music and words.

“Tombstone” cuts the shit. It’s unsettling and raucous, like a train car party full of skeletons. The chorus is a nod to Woody Guthrie’s “Taking It Easy,” and Bob’s punchlines like “The sun’s not yellow, it’s chicken” came from Dylan’s own Tarantula. Author Robert Shelton interprets “The king of the Philistines his soldiers to save/Puts jawbones on their tombstones and flatters their graves” as being a reference to President Lyndon Johnson; Operation Rolling Thunder was in full swing in 1965. “Puts the pied pipers in prison and fattens the slaves/Then sends them out to the jungle” would certainly fit. The preceding scene of John the Baptist and the Commander in Chief is another more direct nod to the prez. But to say “Tombstone” is simply about Vietnam would be reductive. Bob paints a broader picture of America in 1965; riddled with senseless violence, corruption, and abuse of power. See a fraudulent National Bank, or Jack the Ripper hiding his killings behind the mask of a member of the chamberr of commerrrce. Dylan’s not so explicit, but he’s still political!

The train car party slows down. The guys grab their ladies and sway to It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry. Our narrator is absolutely trying to romance a lady, “Don’t the moon look good, mama, shinin’ through the trees?” “Don’t the sun look good goin’ down over the sea?” But if Joan and Sara’s little hospital run-in on the UK tour was any indication, our narrator already has a lady at home! “Don’t my gal look fine when she’s coming after me?” He’s stepped out on her and she’s coming for his ass!

I’m always very interested in how Dylan treats women in song. In his book Wicked Messenger, Mike Marqusee articulated the black-and-white picture of women in Dylan song.

“Sexless Ophelia or the ‘hungry women’ (of “Tom Thumb;”) frigid or predatory; elite or earthy; unattainable or attainable – and either way despised and resented.”

quoted from: Mike Marqusee, Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s (2005.)

Bob’s discography could be used as a prime example of the Madonna-whore complex. The lover of “It Takes A Lot To Laugh” isn’t a glamorous nymph with an arrow and bow. She’s not a prostitute either. “I wanna be your lover, babe, I don’t wanna be your boss” is an example of something truly rare in Bob’s writing: a narratortreating a woman as his equal. Of course, he follows that up with contempt: “Don’t say I never warned you when your train gets lost.” Can’t ever be too straight-forward!

Dylan’s never been known as a “good” singer, but “It Takes A Lot To Laugh” is one of his strong vocal performances on Highway 61. Paul tickling the keys and Mike interjecting with memorable, relaxed, swaggering licks highlight how comfortable Bob sounds on those stretched-out notes. The loping, easy tempo, honky-tonk piano, and laidback drumming are a hint at Dylan’s interest in country music. The fender-bender scene in A Complete Unknown wasn’t just a silly excuse to work Johnny Cash into the story: Bob tried to collab with him all the way back in 1965!

We rock and roll our way into From A Buick 6; a prime moment for our ensemble cast. Bassist Harvey Goldstein rumbles along, hitting all his marks, with Bob jangling and droning away and a bleating harmonica solo over top. (Not to be a boomer about this, but why’d that harmonica have to be so loud?) Mike’s licks electrify the memory of Robert Johnson, “She keeps this four-ten all loaded with lead” is a nod to his “32-20 Blues.” Highway 61 passes through the Delta. “Buick” is another ode to a lover, this one a little rougher around the edges. A “junkyard angel” and “soulful mama,” laying the blanket over his body on his deathbed. Loose lips sink ships, so she “don’t make (him) nervous, she don’t talk too much.” She’s a badass in her own right: “She walks like Bo Diddley and she don’t need no crutch.” She’s the Bonnie to his Clyde, a real ride-or-die bitch. Another woman our narrator sees as his equal.

Paul begins the bitter, stately, at times crass funeral march of one of Highway 61’s sluggers. Ballad of a Thin Man marches on with lead-heavy feet. The dramatic dun-duns, Mike’s humid ambling, and Al’s sweating-bullets-in-church organ make it all the more imposing. Dylan adopts a certain greasy, smug sleaze for Thin Man.

“You walk into the room

With a pencil in your hand,

You see somebody naked and you,

You say, ‘Who is that, man?’

You try so hard but you

Don’t understand,

Just what you will say when you get home

Because something is happening here,

But you don’t know what it is.

Do you, Mr. Jones?”

“Thin Man”’s rhyme scheme, with the last line always rhyming with “Jones,” creates feeling of inevitability. It’ll always come back to Mr. Jones.

I remember YouTube channel Polyphonic had a phenomenal “Thin Man” breakdown about seven years ago now? His analysis leaned into the sexual overtones of the song: the pencil, the sword-swallower, the geek, the cow and milk. He also went into who Mr. Jones might’ve been. Journalists Jeffrey Jones or Horace Judson, Howard Alk, etc., are all contendors, but I don’t know why anyone in their right mind would claim they were Mr. Jones. “Ballad of a Thin Man” is not a song you want to be about you!!

To Robert Shelton, Bob said, “Mr. Jones is like a very weak, ah, well-to-do person.” Elsewhere, “He’s a real person. You know him, but not by that name.” Everyone knows a Mr. Jones. A pompous ass, a killjoy, a bore, a hypocrite.

“You have many contacts

Among the lumberjacks

To get you facts

When someone attacks your imagination.

But nobody has any respect,

Anyway they already expect you

To just give a check to

Tax-deductible charity organizations”

AAAAW! That bridge is another favorite line delivery on the album; with menacing, percussive syncopated force. The disgust with which he says “You’ve read all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books!” is truly impressive.

Again, Dylan is never too serious. He laughs through the opening lines of the song and later hurls, “There oughta be a law against having you around! You should be made to wear earphones!” It’s such a blatant, impish thumbing of the nose you can’t help but laugh. The defining recording of “Thin Man,” though, is far and away Manchester Free Trade Hall. I played it on my Hippie Hour segment. Any and all humor in “Thin Man” has evaporated, Bob just spews venom at his audience. In this moment, they all became Mr. Jones. It’s gleeful and dark. He lost himself in the vitriol of “Thin Man.”

Queen Jane Approximately is the most Blonde On Blonde song on Highway 61, because a. it’s the loosest, and b., it’s the most stoned! The band sounds lightheaded, a little drowsy, and the guitar is delightfully out of tune. Our narrator attempts to show an idealistic woman the realities of her situation; where her optimism helps and where it falters. He’s gentler with this woman than the spoiled subject of “Like A Rolling Stone,” in hopes she might accept him into her world. “Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane?” Though he needles her a bit, he stillmakes a bid for her affection.

Though I understand why “Queen Jane” begins side two of the LP, it’s a foil to “Like A Rolling Stone,” it’s a non-starter compared to the lean, mean track to follow:

“God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son.’

Abe said ‘Man, you must be puttin’ me on.’

God said, ‘No.’

Abe said, ‘What?’

God said, ‘You can do what you want, Abe, but uhh,

Next time you see me comin’, you’d better run!’”

These are the greatest opening lines of any song in rock-and-roll. Not for their content, Bob’s interpretation of the story of God, Abraham, and his son Isaac, but for its delivery. You can tell a story straight, but your delivery colors in the picture. Like “Tombstone Blues,” our title track delivers a warts-and-all picture of America in the mid-1960s. Verse two, with Georgia Sam and poor Howard, is a commentary on race relations. Mack the Finger and Louie the King are pictures of American consumerism and the havoc it wreaks on the environment. Red-white-and-blue shoestrings and a thousand telephones that won’t ring are dumped on the highway. “Now the roving gambler, he was quite bored/He was tryin’ to create a next world war” plainly calls out warmongers in the White House. Bob having this extensive and political examination his title track made a strong statement.

As is that goddamn whistle! A Complete Unknown claims Dylan bought it on the street, Al claims it was his. Whoever it belonged to, it’s boisterous and stupid fun. Oft-overlooked is Dylan’s humming at the end; worthy of any blues master.

Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues feels out-of-place musically, even within the Highway 61 through Blonde On Blonde era. Mike and Bob’s winsome, breezy guitars hint at Bob’s fixation with south-of-the-border exoticism.He’d touch on this in his Basement Tapes era with cuts like “Goin’ to Acapulco,” and fully explored it on Desire. Being that song and album are among my personal favorites of the Dylan canon, I enjoy “Tom Thumb.” It’s pretty. The narrator is a stranger in a strange land; taking comfort in the “hungry women there and they’llreally make a mess outta you” and Sweet Melinda, almost definitely a “lady of the night.”

Words like “pretty” and “beautiful” don’t typically go together with “Bob Dylan.” His lyrics at this time madetheir home in the abrasive and strange. You guys know by now I’m fascinated with endings and destruction. Loss of innocence, end-of-days, Hindu god Shiva, Hades and the Greek underworld. Death and destructioncome up over and over again in my work. If there were a real Desolation Row, it might be New Orleans. The real-life end of Highway 61. The land is wet, fertile, and green. Locals live among above-ground graves. Death is part of the city’s history. Death isn’t to be feared here, it’s another beginning.

“I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead...”

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,

starving, hysterical, naked...”

“They’re selling postcards of the hanging.”

There is only one full stanza of “I”’s from the narrator of “Desolation Row,” and a couple odd lines through the rest of its eleven minutes. Otherwise, it’s “they,” “he,” “she.” “They’re selling postcards of the hanging.” The opening line is based on a true, horrifying event that took place in Dylan’s hometown of Duluth, two decadesbefore Bob was born. Three Black men were falsely accused of rape and hung by an angry mob. A photo of townspeople posing with their bodies became a postcard. The crime wasn’t officially recognized by Duluth until 2003; 73 years after these men were lynched.

Most all the Dylan biographers I’ve cited, including Mark Polizzotti, emphasize how dark the content of “Desolation Row” is.

“As (the song) progresses, detail piles upon detail, image upon image, compelling one to listen, to keep going forward, even as the air through which one is moving darkens to the point of impenetrability.”

quoted from: Mark Polizzotti, 33 1/3: Highway 61 Revisited (2006.)

Despite the grotesque content – hangings, debauched circuses, executions, heart attack machines – that which illuminates the darkest corners of American history, I find “Desolation Row” an oddly comforting song about the end. This might have something to do with how I first heard the song. His Manchester performance was dark,mystical, and weary. Though Charlie McCoy’s flourishing guitar on the album version is romantic, maybe a little much at times, I can’t shake that tired-eyed romanticism I once felt. “As lady and I look out tonight on Desolation Row.” Even if it’s fleeting interactions like Romeo barging in on Cinderella sweeping, or a scrap between T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound (who I think are stand-ins for Alan Lomax and Al Grossman,) you’re never truly alone.

“Desolation” is a prime example of Dylan’s surreal, circus-like world. Cinderella stands with her hands in her pockets Bette Davis-style. The Phantom of the Opera is the priest at the feast. Casanova is put to death, a handful of Shakespearean characters rub shoulders with Einstein disguised as Robin Hood. They sniff drainpipes, recite the alphabet, love each other, hurt each other. Many are name-checked, some are not.

“Praise be to Nero’s Neptune,

The Titanic sails at dawn.

And everybody’s shouting

‘Which Side Are You On?’

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower,

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers.

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow,

And nobody has to think too much

About Desolation Row”

I’m convinced those passengers of the Titanic shouting “Which side are you on?” is a nod to Pete Seeger and the Newport folks. Dylan’s performance drew the line in the sand between the old and new schools, but what does it matter if commercialism is the iceberg and folk music is the Titanic?

The Cains and Abels, Ophelias, and Dr. Filth mill about with faceless characters. They are making love, or else expecting rain. Their lives go on amidst this madness. We, the listeners, are not the Cinderellas or Casanovas. We’re the rest. These are faces and names we’ll never know, as our narrator gave them the Picasso treatment.

“All these people that you mention,

Yes, I know them, they’re quite lame.

I had to rearrange their faces

And give them all another name.”

Moments like this, where Dylan breaks the fourth wall, are magical.

If “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Masters of War,” and Highway 61’s title track are Bob’s pictures of apocalypse, “Desolation Row” is his gentle, romantic, horrifying, beautiful guide to the end.

A phrase I’ve been obsessed with lately is “connective tissue.” They’re beautiful words, for one. Connective; moves perfectly from the back of the throat to the tip of the tongue and teeth and back. Tissue, sounding soft and ending in one of my favorite vowel sounds in the English language. It’s the connection between Roy Orbison and George Harrison, Roy Orbison and Bruce Springsteen. Dylan and Springsteen. Phil Spector, the Ronettes, and the Beach Boys. The Beach Boys and the Beatles. The Beatles and Dylan. Dylan and the Byrds. The fact that Eric Fucking Clapton is mentioned in this review!

Dylan telling Mike Bloomfield “I don’t want you to play any of that B.B. King shit, none of that fucking blues” is pretty ironic considering how indebted to the connective tissue Highway 61 is. It’s an appreciation of Dylan’s intertwined roots; from the Delta blues to the Anthology of American Folk Music, rock-and-roll, and even a lick of country.

Dylan’s always been looking back. See Love and Theft, Shadows In The Night, Triplicate, and him continually rerecording his own stuff because he’s basically the modern American songbook at this point! The more you look at Highway 61, the more incomprehensible it becomes. The scene always changes. Even for Bob. The pavement is laid with winding word command, obscured morals to the stories, and a wiley cut-the-shit band plays us through. But you never travel this same road twice. You get older, wiser. Meaner. You might get left behind at the rest stop a time or two. It’s not any of our trips home, yet on my first listen after several years away, I felt warm and cozy, like getting off the exit on my trip home.

Is Highway quintessential Dylan? I don’t think there’s a “right” answer to this. There have been so many Bobs; across the Bob Johnston-produced albums alone. He contains multitudes. However disorienting and incomprehensible, for fifty minutes, we get to travel the confusing, hostile world of sixty years ago with Bob. If Blonde On Blonde is Bob’s photo diary, Highway 61, Revisited is his road diary. It’s a nod to the authors on his bookshelf and his phonebook, and all the people he loved and betrayed.

What of that diary is fiction and what is reality? Who fucking knows. It’s smart, it’s challenging, at times goofy and weird. You might see your reflection in a guardrail, or the shadow of the one that got away in the headlights. Don’t think too much. Just enjoy the ride.

Personal favorites: “Like A Rolling Stone,” “Tombstone Blues,” “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry,” “Highway 61, Revisited,” “Ballad of a Thin Man,” “Desolation Row”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Boyd, Joe. White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2007 ed.

Crandall, Bill, et. al. “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” Rolling Stone, 12/9/2004.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind The Shades, Take Two. London: Penguin Books, 2001.

Kalet, Hank. “Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited.” PopMatters, 2/7/2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20101112101407/http://www.popmatters.com/pm/review/dylanbob-highway61mft

Kooper, Al. Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ’n’ Roll Survivor. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2008 ed.

Kubernik, Harvey. “Bob Dylan’s ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ Turns 60.” Music Connection, 8/11/2025. https://www.musicconnection.com/bob-dylans-highway-61-revisited-turns-60/

Marcus, Greil. Like A Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads. London: Perseus Books Group, 2005.

Marqusee, Mike. Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005.

Polizzotti, Mark. 33 1/3: Highway 61 Revisited. New York: Bloomsbury, 2006.

Schumacher, Michael. There But for Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs. New York: Hyperion, 1996. https://archive.org/details/therebutforfortu0000schu/mode/2up?q=1965+newport

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. London: Omnibus Press, 2011 ed.

Springsteen, Bruce. “Induction Speech for Bob Dylan.” (Speech, New York, NY, 1/20/1988.) Video recording, YouTube: Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, 2/11/2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=SRu66l3QI_U

Wald, Elijah. Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. New York: Dey Street Books, 2015.

i could hear/ watch/read your writing forever AD. and will never consider anything you say to be redundant. i think that's fair.