The Ballad of The Basement Tapes

- Abigail Devoe

- Aug 11, 2025

- 20 min read

A conglomeration of the incredible past.

Bob Dylan: lead vocals, guitar, piano

The Band:

Levon Helm: drums, vocals, mandolin, bass

Robbie Robertson: guitar, backing vocals, drums

Richard Manuel: vocals, piano, harmonica

Rick Danko: bass, mandolin, backing vocals

Garth Hudson: organ, saxophone, accordion, piano, clavinet

Produced by Bob Dylan and the Band, engineered by Garth Hudson

art by Reid Miles

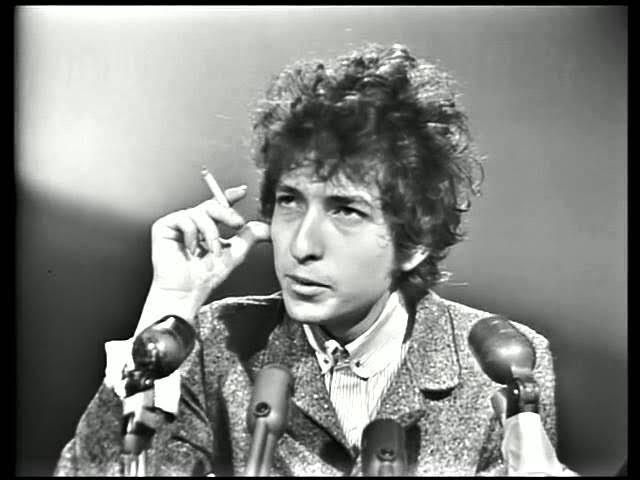

“The reassessment was complex. Who was he dealing with? Why was he dealing with such people? Was the entire ballgame about being Elvis? Why were there those who hailed him as some kind of Messiah? How could he balance the long tours with family life? When would he have time to finish his novel, Tarantula? Was the image shown of him in the upcoming ABC-TV special, his Eat The Document image, the real Bob Dylan? If this special was shown on network TV across the States, that image would be further cemented in the public’s collective memory bank. So was this how the artist wanted to be perceived by millions of casual TV viewers as well as his hardcore faithful?

Dylan said later: 'The turning point was back in Woodstock. A little after the accident. Sitting around one night under a full moon I looked out into the bleak woods and said, 'Something’s gotta change.' There was some business that had to be taken care of.”

quoted from: Sid Griffin, Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band, and the Basement Tapes (2014.)

We don’t need to go over the crash again, do we? It’s like Uncle Ben dying in every Spider-Man reboot ever.

The Story

Whatever happened on July 29th, 1966, it brought Dylan’s plans to a swift, immediate halt. His upcoming world tour was cancelled, much to manager Albert Grossman’s chagrin. Tarantula was postponed indefinitely, Eat The Document rejected. Dylan’s contract with Columbia was up for renewal; he put off re-signing as long as possible. Retreating to Woodstock wasn’t a bad opportunity for him to get back to what he did: writing songs.None of the other bullshit. Suddenly realizing you’re not invincible will do that to a man. He’d do this with the woman he loved by his side. Sara Dylan was not about the rock-and-roll lifestyle. She wanted to settle down and have a family. Bob really loved her and wanted to give her that; he wanted to be her family man. “It takes a woman like your kind to find the man in me.”

Though he wasn't not on the road, Bob's touring band, the Hawks, were still on his payroll. They were involved in Eat The Document and You Are What You Eat, so Grossman suggests the guys move to Woodstock too. Rick Danko finds a pepto-bismol pink eyesore. Just...impressively ugly. But it’s big enough for everyone, and cheap after rent is split four ways. In February of 1967, the Hawks (minus Robbie Robertson) moved into...“Big Pink.” Cue the single most productive year of Dylan’s entire career.

The Hawks set up a makeshift studio in, you guessed it, the basement of Big Pink. Garth Hudson connectedsome mics (one balanced on the boiler!) to a Revox two-track machine and an Altec mixer. Rick remembered, “For ten months...we all met down in the basement and played for two or three hours a day, six days a week. That was it, man. We wrote a lot of songs in that basement. It was incredible!” In no time, the guys established a routine. According to Levon, Bob “started coming over as soon as he’d recovered from his injury, usually at the same time every afternoon, and they’d all go downstairs and play…” Then they’d relocate to his place. “In the afternoons and evenings they’d go back to Big Pink and play for fun in the basement, writing songs for other musicians to cover. Garth’s Revox was used to record these demos, which were sent to Bob’s music publisher in New York.”

Woodstock treats Bob very well creatively. He wrote as many as ten songs a week; including “Tears of Rage” with Richard Manuel, “This Wheel’s On Fire” with Rick, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” and “Nothing Was Delivered.” His musical outlook was shifting. No need for amp stacks in the country! Naturally, he drifted away from rock-and-roll. He remembered his roots, and absorbed stuff from the Hawks. Levon said, “I could tell that hanging out with the boys had helped Bob to find a connection with things we were interested in: blues, rockabilly, R&B. They had rubbed off on him a little.” And, of course, he nabbed a little country from Levon! All great musicians are sponges; all parties benefited handsomely from the cross-pollenation.

You have to remember, the public thought Dylan was a vegetable. After nine months of radio silence and crazy rumors about his condition (possible involvement of the mafia, a CIA assassination plot, you name it,) Dylan granted his first post-retreat interview to the New York Daily News in May of 1967.

When asked what he was up to, he gave the most Dylan answer ever:

“...poring over books by people you never heard of, thinking about where I’m going, and why am I running and am I mixed up too much and what what am I knowing and what am I giving and what am I taking.”

quoted from: Phillipe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guedson, Bob Dylan: All The Songs: The Story Behind Every Track (2015.)

Footnote: Allegedly someone faked a hospital interview? I’ve read about it many times, but cannot find a source. If it ever existed, it seems to be lost media.

“...books by people you never heard of…” Sure, Bob. No one’s heard of King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, or the freaking Bible.

The Basement Tapes (The Songs)

Levon was last to move to Woodstock, from an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. As he arrived, Albert Grossman headed to London with demos in tow. According to the Melody Maker in November of 1967, this tape included “The Mighty Quinn,” “Please Mrs. Henry,” “If Your Memory Serves You Well” (retitled “This Wheel’s On Fire,”) “Ride Me High” (retitled “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,”) “Waters of Oblivion” (retitled “Too Much of Nothing,”) “Tears Of Rage,” and “I Shall Be Released.” Naturally, Grossman’s acts got first pick. Ian and Sylvia recorded “Tears Of Rage” and “This Wheel’s On Fire,” Peter, Paul & Mary release a “Too Much of Nothing,” and Manfred Mann got “The Mighty Quinn”/“Quinn the Eskimo.”

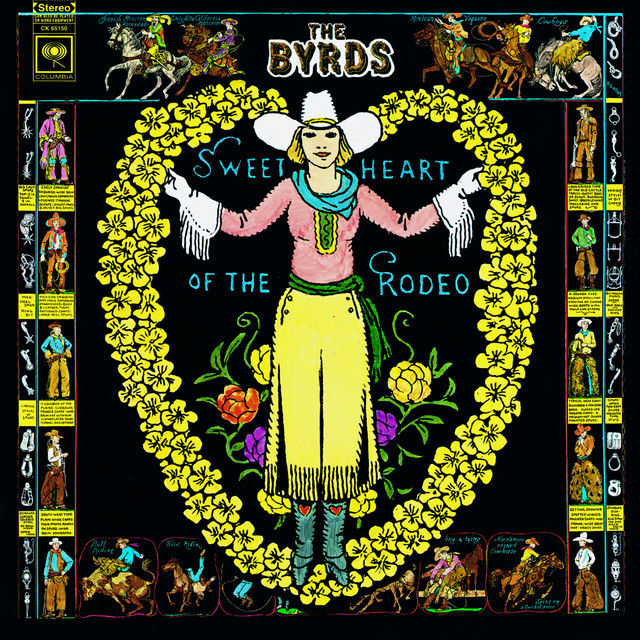

By the time the tapes made it back stateside in very late 1967 or early ’68, seven more songs were copyrighted by Dylan’s publisher; including “Nothing Was Delivered.” This is the iteration that fell into the hands of Byrds bassist Chris Hillman. His band is in the shit right now; having lost Gene Clark, David Crosby, and Michael Clarke in a year. Clearly, they need some Dylan magic! Chris was blown away by what he heard.

“I remember thinking this was a whole album’s worth of good material...All of them were good songs. All of them.”

quoted from: Christopher Hjort and Joe McMichael, So You Want To Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day, 1965-1973 (2008.)

Chris passed tapes to singer Roger McGuinn, who picked “Nothing Was Delivered” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” for the Byrds to record. The latter was the first song they recorded for what would become Sweetheart of the Rodeo; an effort aided by legend-in-the-making Gram Parsons.

At the same time as all of this, Dylan headed to Nashville to record John Wesley Harding. When he returned to Woodstock, he cut “Ruben Remus,” “Don’t Ya Tell Henry,” and “Long Distance Operator” with the band formerly known as the Hawks. In early 1968, they landed a deal with Capitol Records as “the Crackers;” backing Dylan at the Woodie Guthrie memorial concert under this name. Ironically, just as the band signed with Grossman, Dylan splits with him. By the time the band started recording their debut album, they’re officially christened...The Band. Among the songs they cut in New York as their “trial run” for Capitol were “Tears Of Rage” and “This Wheel’s On Fire.” Released June 1968, their debut album also includes “I Shall Be Released.”

Thirteen months after Music From Big Pink’s release, six of the seven demos on Grossman’s tape leaked from Dylan’s publisher. Two Dylan freaks out in LA got ahold of the tape, they reportedly worked at a record distrubutor, they knew a guy who knew a guy...

Great White Wonder was almost certainly not the first rock-and-roll bootleg, but it was definitely the first that was this popular. Its release naturally bore legal trouble, but the guys behind it were blessed with equal parts hubris, smarts, and unbelievable luck. They didn’t actually use Dylan or The Band’s name anywhere on the packaging. It was either a white jacket with the "GREAT WHITE WONDER" text, or just a plain white jacket like my copy. There was no additional text, no track listing, no printed labels. There were no dates on these recordings, either, meaning it could be argued in court that they were made in the lapse between Dylan’s contracts with CBS and Columbia. As for the 1961 and ’62 recordings, Dylan never copyrighted them! All this was going on amidst the dispute between Dylan and Grossman over the rights to Dylan’s catalog.

Not only did White Wonder open Pandora’s box as far as bootlegging went, it completely changed the narrative surrounding Dylan in Woodstock. Sure, people knew about Big Pink, they’d heard the Dylan songs the Band and the Byrds and such had recorded. The narrative was that Dylan’s accident was so severe that from July of 1966 to the fall of 1967, he could not work. After eighteen months of unusual quiet, the world discovered, in fact, he’d been working all this time.

The Basement Tapes (The Album)

Fast-forward to 1975. After a string of underwhelming albums and a handful of studio recordings of Basement Tapes songs, Dylan linked back up with The Band for a 1974 tour. Then his big comeback, Blood On The Tracks. The first leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue that winter brought Dylan and his gaggle of merry pranksters some press. After six years of White Wonder circulation, Dylan finally gave the okay to officially issue some Basement Tapes recordings. Sixteen tracks were selected; augmented by stuff The Band (supposedly) did at Big Pink.

The Basement Tapes (talking about the album now!) are the single most-fabled collection of recordings in the Dylan canon, and one of the most fabled in rock-and-roll history. The only recordings more mythologized are the albums that didn’t happen, like SMiLE. Bob wrote around 100 full songs between February and October of 1967. The tail end of the Basement Tapes era caught the very beginning of John Wesley Harding, and there were those 40 songs he never got around to putting to music! (More on those in my review of the New Basement Tapes album.) Bob wrote something like 150 songs in a calendar year. 150!! That’s unfathomable! And he recorded 46 more covers in that time! The sheer magnitude of his output is impossible not to mythologize. He was recording about as much as he wasn’t.

Sid Griffin identifies Dylan’s supersized basement repertoire as being distinctly American. The days of Carnaby Street suits and rubbing shoulders with the Beatles and Stones were put on ice. The lyrics of The Basement Tapes bear nods to groups like the Coasters in “Million Dollar Bash;” “Along came Jones, emptied the trash. The working title of “Clothes Line Saga” was supposed to be a response to Bobbie Gentry, and “Goin' to Acapulco” might cast its line to the 1963 Elvis movie Fun in Acapulco.

Of all 147 songs (I think that’s the final tally?) Dylan recorded at Woodstock, covers and originals, only onewas not American. What was that song? Flight of the Goddamn Bumblebee.

Going into The Basement Tapes:

1. It’s long,

and 2. it’s not all Dylan.

I’ve covered plenty of double albums before. Some fly by: the White Album, Daydream Nation, Blonde On Blonde, Electric Ladyland, The Wall. Others do not: Exile on Main St., Tommy, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. The Basement Tapes isn’t the longest double album I’ve covered; it’s seventeen minutes shorter than The Lamb. But it makes every minute of its 77-minute run time felt. I think this comes from the tone of the album: laid-back, yet intensely insular. As the woman in the room, I picture the basement to be an environmentI’d have wandered in and out of. Make another pot of coffee, grab some food. Tend to some other business. Be alittle less attached to the whole thing. The double-album format forces me to sit in the basement as one of the guys. Months of futzing is trimmed to 77 minutes, and you’re expected to be in the room for all of it.

My main critique of The Basement Tapes is that it’s a lot of midtempo and downtempo songs. If you’re not in the mood for damp air and the smell of wood oil, this will give you cabin fever! After so much of the same, I lost focus at times. But I don’t fault the music for that. No one thought the Basement Tapes would be much of anything, let alone an album.

There are obviously incomplete inclusions; “Apple Suckling Tree,” “Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread,” and“Tiny Montgomery” are dull against some of the all-time great tunes presented in this package. There are bizarre omissions abound. Not including a Dylan and The Band “I Shall Be Released” takes the cake. It was playedthree times at Woodstock alone! Why Columbia wouldn’t include it is beyond me. “The Mighty Quinn” isanother bizarre exclusion.

Then comes the sequencing. You want to set the ballad of the Basement Tapes against the unraveling of the Woodstock generation? You end it with the guys peeling down the dirt road away from Woodstock. “Now you must provide some answers/For what you sold has not been received.” End credits. Instead, we have three more scenes following “Nothing Was Delivered.” So I guess The Basement Tapes is like...the world’s chillest Tarantino film? Nobody dies, no white guys saying the N word with a hard R. (We have to wait until Desire for that.) Maybe some shots of bare feet? But everything’s out of order.

Track-By-Track

The Basement Tapes starts in order, with ace sequence of Odds and Ends, Orange Juice Blues, and Million Dollar Bash. If we were to slot The Basement Tapes in chronologically by when it was recorded, it would come between Blonde On Blonde and John Wesley Harding. Sonically, “Odds and Ends” is the natural place to start. Thanks to Robbie’s lead guitar work, the song still has some of that R&B, rock-and-roll feel lingering from the days of the houndstooth suit and his Hawks. ’66 Dylan’s sense of defiance remains too.

“You know what I’m saying and you know what I mean.

From now on you’d best get on someone else,

While you’re doing it, keep that juice to yourself.”

“Odds and Ends” is about wasting time, either in a relationship or simply by pleasing other people. “You promised to love me, but what do I see?/Just you comin’ in spillin’ juice over me.” It’s less than two minutes long, but this opener doesn’t feel incomplete.

If The Basement Tapes were a movie, The Band is the Canadian spaghetti western B-plot.

They come riding in on “Orange Juice Blues.” It’s clever to keep the juice theme going, even if it’s not in the lyrics at all. This formally introduces our sidemen, who aren’t such sidemen anymore. Their roots are in the blues, with a twist of country, their sharp musicianship bears chemistry real kin have, and Garth Hudson’s multi-instrumentalist talents do not go unnoticed.

Some interpretations say “Million Dollar Bash” is another swipe at Warhol...I don’t buy it. About the song, Bobhimself said: “It was the Summer of Love, but we weren’t there, so you know, we did our thing. We wrote ‘Million Dollar Bash,’ you know, to go along with the Summer of Love.” If this really is the Summer of Love, the titular Bash might have been Monterey Pop. The Mamas and The Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, the Who, and Jimi Hendrix all played. The Beach Boys were supposed to be there, but bailed. There’s nothing remotely psychedelic or ’60s pop confection about The Basement Tapes, that’s for sure! There’s that prominent organ Bob so loved, probably played by Garth, and lyrics that, while odd, aren’t odd in the esoteric way. Dylan loved to play with how words sounded together, to varying results. “Million Dollar Bash” happens to be so funny. “Cheeks in a chunk with his cheese in the cash,” his particular annunciation of “PoTa-Toes,” and what has to be an all-timer:

“I looked at my watch, I looked at my wrist,

I punched myself in the face with my fist!”

What if some of Dylan’s wordplay at this time was inspired by Sara’s grocery lists? Think about it. Therehappens to be a lot of puns and imagery based around grocery items in these songs. Milk, butter, eggs. Cheese, juice, sweet cream. PoTa-Toes. Laundry soap.

Yazoo Street Scandal moves things along by cutting through the fuzz. It was clearly recorded out of the basement at a different facility with different instruments. You’re fooling no one here! The same goes with Katie’s Been Gone; it literally sounds just like a Big Pink session...

...because it was!

The Basement Tapes came with a bit of scandal. In a review of a later Music From Big Pink deluxe edition, Dave Hopkins called “Katie’s Been Gone” out as being recorded in NY or LA during Big Pink sessions and not the Basement. It’s the exact same take! Levon himself confirmed in his book that the tapes weren’t 100% “basement.” “The twenty songs had been picked from the demos Garth had recorded in the basement of Big Pink back in 1967, sweetened in some cases by guitar overdubs recorded by Robbie that year at Shangri-La.”Due to that quote being super poorly worded, many sources misinterpret the overdubs taking place in 1975. I got confused at first too. The Basement Tapes’s release caused dissent within the Band, too. Capitol had them on probation at the time, so the album didn’t count towards their record deal.

I’m hesitant to express my admiration for these tracks as they’re so clearly outside the scope, but they’re amongmy favorites. “Yazoo” has an interesting, almost funk bassline, and the wagon-wheel bounce of the riff makesfor a fun listen. I do wonder if the tape was sped up to alter the pitch – I nearly mistook Levon for a ’76 Dylan!

One of the great pleasures of The Basement Tapes is hearing the creative breakthrough The Band in real-time. About recording Ain’t No More Cane, Levon said:

“One of the things we’d always loved about soul music was the way groups like the Staple Singers and the Impressions would stack those individual voices on top of one another, each voice coming in at a different time until you got this blend that was just magic. So when we cut…‘Ain’t No More Cane’ in our basement, we tried to do it like that, with different voices...Our version started with me singing the first verse. Then Richard did the second, Robbie sang the third, and Rick brought it home. We all sang harmony on the chorus, and Garth layered his accordion over everything. Richard played the drums, so I played mandolin. That recording...was a breakthrough. With those multiple voices and jumbled instruments we discovered our sound.”

quoted from: Levon Helm with Stephen Davis, This Wheel’s On Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of The Band (2000.)

They had a beautiful grasp on melody, too. I love “Katie”’s melody and gentle push-pull of the tempo. “Ain’t No More Cane,” with Richard on drums, Levon on mandolin, and I think Garth on accordion is lovely as well. It has one of the most memorable melodies on the album. The Band paired best with dual piano and organ; like on Bessie Smith and Ruben Remus. The latter has rickety guitar, and maybe the most Zappa title I’ve ever seen anywhere that isn’t Zappa. Long Distance Operator brings some of the heavy-footed attitude “Cripple Creek” would have. Interjections of saxophone give a smoky atmosphere. Unfortunately, it feels unfinished.

“It’s a wicked life, but what the hell?” Goin' To Acapulco was one of my old favorites, it still is a favorite. Its mournful country-rock feel is powered by breathless, end-of-the-night-at-the-dance-hall organ. Our lonely narrator nuzzles up to his Rose-Marie; either a barmaid or a “lady of the night.” The Band’s moaning harmonies are stunning; like being out in the desert at dusk, endless sky with nothing for miles, and hearing wolves crying in the background. It pulls the very best out of Dylan. When he lets loose into that pained, strained “Yeeeeeah!” over a proto-“The Weight” guitar lick, it’s sublime. “Acapulco” is a beautifully illustrative song. I can see the pink glow of the sky, I can smell the tobacco. Some neo-cosmic-country group needs to hurry up and record this. It’s one of the strongest songs of the whole lot.

Speaking of a bar: there are quite a few drunken romps on The Basement Tapes. I get the feeling the beer and wine were a-flowin’! Lo and Behold rumbles along on sea legs. Absolutely an exercise in the classic Dylan technique of Saying Words, this guy goes on an impossible journey to San Antonio and Tennessee. He pursues Moby Dick, ends up in Chicken Town, he’s buying moose, I can only describe this as all-American delirium.

Please Mrs. Henry is super drunk. The guy outright admits he’s had “two beers” and bargains with the titular innkeeper’s wife to let him practically stick his face under the tap...and other places. We’re the voyeurs in the hall; dropping in on the stream-of-consciousness slurring of a drunk guy simping for Mrs. Henry. She drags him to his room upstairs, presumably by the ear. “I’m a sweet bourbon daddy and tonight I am blue/I’m a thousand years old and I’m a generous bomb.” He’s literally piss drunk! “If I walk much farther my crane’s gonna leak!” Not even Dylan can hold his laughter.

I’ve analyzed Tears Of Rage before in my Big Pink episode. I won’t be going into the nitty-gritty of this, “This Wheel’s On Fire,” or You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere. Especially the latter because I literally just talked about it! Andthe Byrds’ arrangement is very close to Dylan’s. But I want to add an additional “Tears Of Rage” interpretationhere. Bob Dylan: All The Songs raises “Tears Of Rage” as being from the point of view of a Vietnam war veteran. He comes home to experience the government’s neglect of veterans first-hand; he “discovered no one would be true.” He risked his life and his friends died for nothing. “Oh what dear daughter ’neath the sun could treat a father so?” Is an intriguing line. It’s probably a reference to King Lear, but I think of people calling this country “she.” And Lady Liberty falls. Richard Manuel’s impossibly high voice is heart-rending on thisrecording. Dylan’s more a dirge than The Band’s.

Disc two of The Basement Tapes kicks off with Too Much of Nothing; more Shakespeare wrapped in a T.S. Eliot diss track. The “Valerie and Vivienne” in the lyrics were the names of Eliot’s two wives. After he separated from Vivienne, she was left in a mental institution. He didn’t call or visit her once. Then, he married Valerie, who was a whopping 38 years younger than him. Talk about a dick move!

I love “Too Much”’s guitar work. It curls around the song like thin green leaves on a vine. The lyrics are abouthow scarcity – either perceived or literal – brings out the worst in people. As Bob describes it’s human nature, the instrumentation ascends and ascends, creating tension.

“But it’s all been done before,

It’s all been written in the book

And when there’s too much of nothing

Nobody should look”

I thought of the story of Lot; his wife looked back as the family fled the city of Sodom and was turned into a pillar of salt. The tension bursts into the group-vocal chorus with a gratuitous swath on the piano keys.

Hearing Crash On The Levee after so long, I can hear the influence on what The New Basement Tapes did; particularly the reverb on Bob’s vocals. But overall, I hear ’65 Dylan. This is a slowed-down “Highway 61,” right down to the whiny “AAAOOww!”s.

I’ve decided to set Don’t Ya Tell Henry apart from the other Band songs because it’s a distillation of everything they did right. The guitar has more than a twist of Chuck Berry. Levon’s drumming keeps an otherwise-rambunctious energy sturdy and cool. Agile fingers tickle the keys, and the stop-time is infectious. Levon hollers over this rock-and-blues and tells it to us straight: “I went down to the whorehouse the other night, I was lookin around, I was outta sight.” I like to think this is set in the same universe as “Please Mrs. Henry;” the melodies bear some similarity. The narrator of “Mrs. Henry” somehow did sleep with her and is now running from Mr. Henry; while still very drunk!

Open The Door Homer was originally titled “Open The Door Richard;” apparently a reference to the punchline of an elaborate Dusty Fletcher and John Mason gag. Why “Richard” was retitled “Homer” is anybody’s guess. The lyric is still “Richard.” Maybe it’s because the Bible is an epic in and of itself. Some of the lyrics arereminiscent of a sermon: “Remember when you’re out there/Trying to heal the sick/That you must always first forgive them.” That’s, like, Jesus’s whole M.O.

Dylan and the Band’s This Wheel’s On Fire sounds shackled to the ground. Coming back to what I said about closing The Basement Tapes with the end of the happy hippie ’60s, this provides a darker close. It’s a desolate interpretation. Indeed, this sequencing was assembled by people who saw 1968, ’69, and ’70 through. This wheel did, in fact, explode, and it had far-reaching consequences across the 1970s.

Sooner or later, the party at Big Pink had to end. Once favored for its seclusion, word got out. People inevitably turned up looking for Bob, and the Band cleared out. Listening to The Basement Tapes, I’m trapped between thesurrealist slice-of-life movie I imagine it to be and its actual intent: just a roll of demos. It exists in a weird liminal space between the two. Greil Marcus described the same limbo and duplicity in his liner notes for the album:

“...a testing and a discovery of roots and memory; it might be why the Basement Tapes are, if anything, more compelling today than when they were first made, no more likely to fade than Elvis’s ‘Mystery Train’ or Robert Johnson’s ‘Love in Vain’...(it) matters here not as an ‘influence’ and not as a ‘source.’ It is simply that one side of The Basement Tapes casts the shadow of such things and, in turn, is shadowed by them.”

quoted from: Greil Marcus, The Basement Tapes liner notes (1975)

The New Basement Tapes member Taylor Goldsmith said The Basement Tapes was “just the coolest thing that I could’ve imagined getting ahold of. It’s sort of like, ‘Oh, I’ve stumbled upon a secret that wasn’t ever meant for me to hear.’” That’s the big thing I had to remember when evaluating The Basement Tapes. This was never meant for you, me, or anyone, to hear. Robbie said, “We weren’t making a record. We were just fooling around. The purpose was whatever comes into anybody’s mind, we’ll put it down on this...Shitty little tape recorder...We had that freedom of thinking, ‘Well, no one’s ever gonna hear this anyway, so what’s the difference?’”

It’s a fascinating articulation of an artist’s heel-turn. The man changes. He cut his hair, ditched the polka dots for wire-rim glasses and suspenders. He’s in his mid-20s; a time in your life you have to get it together. No more dicking around, vomiting in cabs. This is real life now. Then, the music changes. He plugs in, then unplugs. He’s returning to his roots, settling in. He never writes quite this much in one period again. Retreating didn’t dim his star, it only brightened it. That’s the luck of the devil.

Though it sounds naturalistic, it’s not. It’s a little Hollywood; studio magic on The Band songs. There’s references to epic stories, on page and in screen, old world and new, east and west. Belly dancer and ballerina. The Basement Tapes aren’t supposed to have any overarching narrative. This isn’t the big-screen follow-up I so desperately want for A Complete Unknown. There’s nothing destiny about it. It’s a hodgepodge of stuff Columbia shooshed out as soon as Bob was okay with it.

As the man himself said, “Nothing is worth analyzing – you learn from a conglomeration of the incredible past.”

Personal favorites: “Odds and Ends,” “Million Dollar Bash,” “Yazoo Street Scandal,” “Goin’ to Acapulco,” “Lo and Behold,” “Tears of Rage,” “Too Much of Nothing,” “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “Nothing Was Delivered,” “Long Distance Operator,” “This Wheel’s On Fire”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Dylan, Bob. Tarantula. London: Harper Perennial, 2005 ed.

Griffin, Sid. Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band, and The Basement Tapes. London: Jawbone Press, 2014 ed.

Helm, Levon, with Stephen Davis. This Wheel’s On Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of The Band. Chicago: A Capella Press, 2000.

Hjort, Christopher, and Joe McMichael. So You Want To Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day, 1965-1973. London: Jawbone Press, 2008.

Hoskyns, Barney. Across The Great Divide: The Band and America. New York: Hyperion, 1993.

Jones, Nick. “Dylan Today.” Melody Maker, 11/4/1967. https://www.worldradiohistory.com/UK/Melody-Maker/60s/67/Melody-Maker-1967-1104.pdf

Jones, Sam, dir. Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued. Beware Doll Inc.: Prime Video, 2014.

Margotin, Phillipe, and Jean-Michel Guesdon. Bob Dylan: All The Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2015.

Roher, Daniel, dir. Once We Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band. Magnolia Pictures, 2019.

Simmons, Michael. “The Making of The Band’s Music From Big Pink.” Mojo issue 299, 10/2018. https://www.mojo4music.com/articles/stories/the-making-of-the-bands-music-from-big-pink/

Wenner, Jann. “Dylan’s Basement Tapes Should Be Released.” Rolling Stone, 6/22/1968. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/dylans-basement-tape-should-be-released-233261/

Black market recordings that changed music history, now there's a can of worms, eh?

at times everyone sounds like they're having a time of it. it seeps into the music and that's ok. some good music ( i like hudson's playing, he gets honorably mentioned here,in particular ) and some, i think it so i'll say it, some daft almost pointless tracks.

they are secluded in there though, almost reclusive, and there's a real musical revolution going on above. in England the sources of rivers that will become metal, folk fusion, progressive, are bubbling. that's not a denial of the strength of the back to the roots movement, the beatles would join hands with it at one point, it's just a parallel thought. perhaps it's the very differences that are exciting as we move…