John Cale - Paris 1919

- Abigail Devoe

- Dec 8, 2025

- 19 min read

Or: a love letter to the fish who swims down.

John Cale tried to hide his heart on Paris 1919. Thankfully, it doesn't work. john cale paris 1919

John Cale: lead vocals, viola, acoustic guitar, piano/keys

Lowell George: guitar

Wilton Felder: bass

Richie Hayward: drums

UCLA Symphony Orchestra, directed by J. Druckman

Produced by Chris Thomas

art by Mike Salisbury

This is part two of a three-part miniseries on what the Velvet Underground did after the Velvet Underground. To read part one, click here.

When I developed the concept for this miniseries, I thought I’d have to introduce this guy as like the lesser-known one. But at 83 years old, he’s been suddenly catapulted back into the pop culture consciousness through collaborating with Charli XCX for the Wuthering Heights soundtrack! Just goes to show this guy still is and always has been one of rock-and-roll’s great experimenters.

But this album is not drone, noise, or a morose German lady singing over a harmonium. It’s full of sweet and totally original confections, but it took a whole lot of sour to get there.

After the ejection of Nico, John Cale was the next of the classic-era lineup to be ousted from the Velvet Underground. Co-founder Lou Reed felt threatened, as he so often did with his collaborators. (I’m not dissing Lou by saying this, I’m noting the pattern he established with Nico and carried on with Mick Ronson and David Bowie.) Through the tough production of White Light White Heat, John realized him and Lou just had fundamentally different philosophies about making art.

“Although we both knew we did good work together, he did not feel that the quality justified continuing. It was a conceit of mine (and maybe still is) that art demanded that you create it. It was there as a facilitator. It made me know more of who I was, and I enjoyed it...If your failure to get along with someone caused paralysis, then it was indeed pointless, but I never felt that way about our collaboration...”

quoted from: John Cale with Victor Bockris, What’s Welsh For Zen: The Autobiography of John Cale (1999.)

After White Light White Heat, Lou lead the charge to fire John from the Velvets. There are several different tellings of this event. Victor Bockris asserts the whole band was to go out to lunch together. John didn’t show (he makes it sound like this was a recurring thing,) so he was out. Version number two, John’s version, says Lou met bandmates Sterling Morrison and Mo Tucker at a restaurant. Lou gave the other two an ultimatum, “If John goes on this next tour, I’m not going.” So he forced their hands to fire him. And a third version follows that outline, but has Lou flaking on the band meeting in which John was to be fired, leaving Sterling and Mo to do his dirty work. Which is one of the most Lou Reed things I’ve ever heard! John said, “I thought (and still do think) we could have done great things together. I am not belittling the past at all. I honestly think the best is unrealized. I also think I can find it by myself.”

So that’s what he did. He found it by himself and went solo. Now, let’s speedrun of everything that’s happened since John left the band.

When I say “went solo,” he didn’t immediately go solo like Nico did after the Velvets. Though he received a two-album deal with CBS Records right after he left, John’s first inclination was to become a producer. He had the musical knowledge and ability to guide a musician through the making of their album, that’s for sure. And he believed he could develop the technical ability. What he didn’t have yet was the confidence. Losing his job hurt his former child prodigy ego. “I needed to go out and prove to myself that I was my own person again. In that way Lou did me a favour.”

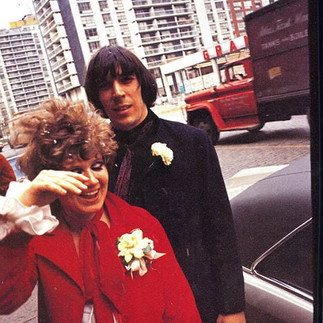

Who inspired him to be his own person again? His first wife, Betsey Johnson. Yes, that Betsey Johnson!

Having her around made John want to be a maverick himself. He didn’t want to use Betsey’s success as a crutch. He wanted her to be her own businesswoman and him to be his own artist.

He’d written songs before; giving “Winter Song” and “Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams” to Nico for her Chelsea Girl LP. He’d sang before, taking lead on “The Gift” with the Velvets. Betsey got John writing his own songs, and he wrote every day. It seems strong women brought out the best in him because the first – and among the best production – work he ever did was for Nico. He produced her game-changing The Marble Index, and Desertshore to follow. It was her who got him arranging. “I didn't know I could arrange, but then I got lucky and found a very strong personality like Nico who threw me against the wall, and I had to bounce back.”

In 1969, John played on and produced Church of Anthrax with Terry Riley, but it went unreleased for another two years. In those years John produced and played on the Stooges’ self-titled album! Jac Holzman loved what he did with The Marble Index (even if critics hated it and said it made them want to kill themselves,) so he was tapped for the Stooges. What a fucking learning curve that was! John says to this day, his two greatest challenges were recording Patti Smith and the Stooges.

John also recorded Vintage Violence, played session man for Mike Heron, his friendship with Joe Boyd had him working with Nick Drake...and he was called in to aid the Velvets during Loaded production. (The mental image of everyone Lou Reed tried to get rid of coming back in some way is very funny.)

CBS didn’t like Vintage Violence, but they didn’t drop John after his two-album deal was up. Instead, they had him developing quadrophonic mixes of albums. It was tedious work, and the perfect opportunity for him to get hooked on all sorts of shit. Before long, he was at the end of his tether. Him and Betsey lived totally different lives, his marriage was all but over. His circle of New York friends had mostly moved on. He was working on this quadrophonic shit from six at night to two o’clock in the morning even though he really didn’t believe in it, and he was sick of being addicted to heroin.

So he made a change. He moved to the west coast, quit heroin cold turkey, left his job at CBS for Warner Bros., and is signed to Reprise Records. But before he left, he saw the Velvet Underground’s first superfan and the woman who tipped them off to Andy Warhol in the first place, Brigid Polk, one more time. Just like Lou used to play her VU songs, John played her “A Child’s Christmas In Wales.”

As soon as he made it to LA in 1971, he got hooked on cocaine. He released The Academy in Peril, but ultimately squandered his opportunity with Warner Bros. as he’d ran up a $120,000 bill traveling to a castle in England to record it! And he remarried to Cindy Wells, AKA Miss Cynderella of the GTOs. I have to be honest, John does not look good when talking about his marriage to Cindy in his book. She didn’t really do anything besides have a complete breakdown after Miss Christine passed...and the whole “The bugger in the short sleeves fucked my wife” thing. John describes it as “the most destructive relationship (he) ever had.” Cindy had to be institutionalized after Christine’s passing, and after two more brutal years for them both, John left.

Come 1972, John is in pretty much the same spot as he was in New York. His second marriage is already doomed, he’s addicted to coke, and now he’s six figures in debt!

“I couldn’t deal with Warner Bros., I couldn't deal with Cindy, I couldn’t deal with myself.”

quoted from: John Cale with Victor Bockris, What’s Welsh For Zen: The Autobiography of John Cale (1999.)

John spun out right into the path of producer Chris Thomas, who had just left the tutelage of George Martin for LA himself. There were some weird similarities between the two: Chris’s mother was not only also Welsh, but she knew John’s mother’s boss in the school system she taught at. Artist and producer got on famously. They got into crazy antics together, like Chris clinging onto the hood of John’s car as he sped up and down Sunset Boulevard! “...we had a whale of a time doing this thing,” he remembered. He felt this relaxed, friendly environment worked in the material’s favor.

How did an album like Paris 1919 happen? It seems unlikely considering John’s past material, and who John is as an artist.

He didn’t grow up with pop music. He was a child prodigy. He was set to study under Leonard Bernstein before changing his mind and moving to New York where he played under La Monte Young. He hated folk music, deeming it pointless. Like Lou Reed, he hated hippie shit. Through him, John got a feel for pop songwriting. The Paris material in particular was inspired by how Jackson Browne wrote; he was intimately familiar with style, as Nico had recorded his songs for Chelsea Girl. He liked how Jackson could make a mean song sound like a love song; “the nicest ways of saying something really ugly.”

Now that we know the personal strife that wrote the lyrics of Paris, I want to zoom out a bit so we can see where the music came from. In 1967, the same year the Velvet Underground debuted, the Moody Blues reinvent themselves with Days of Future Passed. Other groups like the Kinks had tried their hand before the Moodies, but Days of Future Passed was the first really successful combination of classical music orchestration and rock-and-roll. Of course, classical sensibilities in pop around for a long time. See Pet Sounds and what Brian Wilson was trying to do with SMiLE, the Bee Gees’ utterly perplexing Odessa, and Procol Harum; whom Chris Thomas had worked with. John originally wanted to go full steam ahead in the direction of classical music after the failure of Vintage Violence. But then he heard Procol Harum's 1972 live album with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra. It got him thinking about combining classical music with rock-and-roll. Being in LA in the early seventies, he was hearing more rock-and-roll than ever. So he thought, “Why don’t I write arrangements for this style of music?”

John and Chris selected the criminally underrated Little Feat to be the band, and Motown Records session man Wilton Felder on bass. Paris 1919 was recorded at Sunwest Studios in LA. Interestingly, the overdubs for Neil Young’s much-maligned self-titled album were recorded here. Despite the cocaine-fueled insanity of sessions, this was the most time that had gone into any of John’s recordings, solo or otherwise, to date. His previous solo albums, collabs, and the Velvets’ operations were all designed to be off-the-cuff.

As not to risk redundance, I’ll start my review with this: where his counterpart couldn’t really “sing” in the conventional sense, by God, John Cale could sing. John has of the most beautiful and unique male voices in all of rock-and-roll. His accent is lovely and so pleasing to the ear, his chest voice deep in tone and naturally resonant. It’s the best part of every single song on this album.

Before I proper gush over the music, let’s do some album title analysis: Paris 1919. When I hear that title, I think romance. I think absinthe ads and the Metropolitan signs. I think the Paris Peace Conference. The halcyon days of 1920s Europe, the time of his parents’ childhoods. The album art invokes the era; with soft lines, a dreamy Mucha color palette of creams and browns, the look of early photography, and of course the classic art nouveau lettering. (I feel like I’ve seen that specific lettering somewhere before, but I can’t put my finger on it. If you know what this is referencing, please help me out in the comments!) The Edwardian era into the twenties had a moment in the late sixties through the early seventies; see all the art nouveau influences in psychedelia and the popularity of the Biba boutique. Paris isn’t much of a concept album, but John does repeatedly reference this period in the lyrics. Overall, when I hear the title Paris 1919, I think peace, romanticism, beauty, and pre-World War II excess. A last flash of innocence before the 1930s. The music of Paris embodies all this and more.

A Child’s Christmas In Wales just about knocked me on my ass when I first heard it. I was so blown away, I had to go back and play it again before preceding with the rest of the album! “Child’s Christmas” has a stunning interplay of piano and shimmering organ, two of John’s instruments, with layered guitar and slide guitar. His vocals get a bit lost in how ornate the arrangements are, but listen to Wilton’s fills. This is a bright, shiny, optimistic, and catchy pop arrangement to juxtapose John’s absolutely odd writing; which we get the first taste of.

“A Child’s Christmas In Wales” is named for a Dylan Thomas work, but other than this, it doesn’t bear much of any similarity. Thomas’s story lacks the oranges and the cattle, but there is mistletoe. Another one of Thomas’s works, (Ballad of the) "Long Legged Bait," is name-checked as well.

John’s lyricism is very sparse. It’s not like Lou’s “Perfect Day” only using 40-some-odd words, it’s not sparse and precise like that. John’s stripped any and all identifying features out of his lyrics, leaving only the images. I see how people could get tripped up by this quality in his writing. He really makes you work for it! He won’t say all the childhood holidays bleed into one when remembered thirty years down the line, like they did for Dylan Thomas. He’ll say, “With mistletoe and candle green/To Halloween we go.” He won’t say blood oranges were sliced on a butcher’s block, he’ll say, “Ten murdered oranges bled on board a ship.” He won’t directly reference going to church but he will describe, “Then wearily the footsteps walked/The hallelujah crowds” and “Perimeters of nails/Perceived the mama’s golden touch,” alluding to Jesus and Mary. I haven’t seen anyone else catch that Sebastopol is probably a double reference; Tolstoy fought in the siege of Sebastopol, Sebastopol is also a city in John’s new home of California. Adrianopolis was another famous battle site. John’s likening himself to a wandering artist fresh from battle.

Where the lyrics get positively impenetrable is Hanky Panky Nohow. The music is made for a gentle, romantic ballad; with cello, violins, acoustic guitar, and a quaint little tambourine. John’s organ glides over the outtro in one long note. It’s pretty, but as far as drones go, I prefer the alternate version on the 2006 Paris rerelease.

At least some of “Nohow” gets existential:

“Nothing scares me more than religion at my door

I never answer panic knocking

Falling down the stairs upon the law

What law?

There’s a law for everything...”

A lot of outside factors bearing down on any person can cause them to shut the door on everything. “There’s a law for everything,” nature and man, but was man ever supposed to be this advanced worrying about church collections and taxes?

“There’s a name for everything

And for elephants that sing to feed

The cows that agriculture won’t allow”

I think this is a jab at the music industry? The elephants would be the artists, singing to feed the beasts running the labels. However aggressively evasive John’s lyricism is, the “Hanky-panky-nohow” hook is catchy as hell.

Speaking of greedy bigwig types, “Crocodiles and men” – one in the same – gamble everything away with loaded dice on The Endless Plain of Fortune. It could just as easily be a picture of excess of the roaring twenties, as it is an allusion to the excess of a rock-and-roller in the seventies. The thesis statement of the song is the observation that, “It’s gold that eats the heart away and leaves the bones to dry.” Money makes you cruel and greed will waste you away; as greed has wasted away the characters of this song. “Endless Plain” is anchored with a big, dramatic arrangement. Every once in a while, you’ll hear a slide guitar peek out from under the heavy velvet drapes. Otherwise, “Endless Plain” is dominated by brass and strings. The full orchestra is operating on full power. Listen to how the brass crests and falls back under the tide, or the horns’ dissonant stab after John sings, “Gendarmerie,” (a little French for you,) “and all, that’s all/The radio man...” If that’s not enough to dazzle you, hang tight for the full heartrending fanfare at the end. It’s one of the biggest moments I’ve heard on a pop record, standing ten stories tall.

To think John himself arranged all of this. This will sound trite I’m sure, but what a talent. You just have to bask in it, really. Very rarely do we have an artist writing their own arrangements. They sometimes overpower his soft voice (not soft in volume, soft in tone.) But it’s fucking stunning to hear, so I can deal with that.

Gently emerging from behind the velvet rope is the closest to a genuine, no-strings-attached love song as a prickly guy like John is capable of. Acoustic guitar chords are softly plucked for a few bars, perking your ear up after the bombastic fanfare of “Endless Plain.” Shuffling drums are played with brushes as sparse bass and light guitar accents build an utterly timeless instrumental. It almost has a country slant thanks to Little Feat; they incorporate those classic clicking country drums and lonely slide guitar. It’s delicate and sensual, like the smell of the perfumed love letter which our narrator responds to.

“Andalucia, when can I see ya?

When it is snowing out again?

Farmer John wants you, louder and softer,

Closer and nearer, then again.”

“Andalu-cia, when can I see ya” is such a 1960s bubblegum-pop rhyme. It bears an impeccable melody. “Farmer John” is our loverboy being self-deprecating. He’s simple, from humble beginnings. Old Farmer John wants a wife. We can deduce our Andalucia is the opposite of all these things: young, beautiful, sophisticated, of a higher pedigree. He wants her “louder and softer, closer and nearer, then again” coupled with “Needing you, taking you, keeping you...”

...John is being horny on main.

But I said earlier that Andalucia is the closest to a straight love song John is capable of. The last line of that verse, and the way John’s voice cracks on, “Leaving you,” changes everything. This guy is writing to his lover who he hasn’t seen in over a year. “Your face doesn’t alter and your words never falter.” He thinks of her so much that her face and the sound of her voice are still fresh in his mind. When he hits his falsetto as he cries, “I love you,” it’s hard for me not to melt into my quilts and sigh.

“I’ll be here waiting, later and later/Hoping the night will go away.” The night won’t go away until Andalucia returns. She is his light.

“When you’d made up your mind not to come

And I couldn't persuade you or wait till tomorrow

Oh pass the time...”

Wow. Wow wow wow! What a fucking stunning way to phrase him losing her. Two lovers have become ships passing in the night, and it’s not certain if our Farmer John will ever see his Andalucia again. The song fades out before we get her response.

All the greatest love songs have that element of uncertainty. “You’re asking me will my love grow, I don’t know...Stick around and it may show,” “I may not always love you/But long as there are stars above you.” That voice singing those lyrics over that arrangement makes “Andalucia” one of the greatest love songs of all time, as far as I’m concerned.

You didn’t think someone could write a rock-and-roll song about the Scottish play? Think again!

Our side one closer blows the doors open with a rocker named Macbeth. Unlike “Child’s Christmas” which bears virtually no similarity to its namesake work, John namechecks Banquo, alludes to conniving Lady Macbeth, and spells out the general’s fate in a shallow grave at the hands of Macduff. “Alas for poor Macbeth/He found a shallow grave/But better than a painful death/And quicker than his dying breath.” I don’t know what Shakespeare has to do with early twentieth-century Europe, but “Macbeth” definitely tickles John’s penchant for literary references. He was proud of this number, it’s pretty far out of his comfort zone, but it does stick out like a sore thumb against the rest of Paris. Little Feat and Wilton’s Motown basslines gets to shine, they’re sharp as a tack. Lowell even gets a searing guitar solo! Hearing John push his normally plaintive, soft voice into a rock-and-roll scream is exciting.

Turning over the record brings a stark stylistic shift; our title track strips all the rock-and-roll and is scored entirely by the orchestra. It’d be a very unlikely greatest hit for anyone else, but it’s totally likely for John Cale! Paris 1919 is about the joy felt that World War I was officially over after the Paris conference, but the people are still dissatisfied. This mood is illustrated by the line, “The crowds begin complaining/As the Beaujolais is raining/Down on the darkened meetings on the Champs-Elysees.” Some live in excess, some in live in poverty. Some live in peace with swooning strings and birds chirping and the faintest “ooh”s, some conspire in the shadows for something even worse. The Wikipedia page for this also suggests “Paris” may be about a wedding. There are wedding bells in the song, and John appears to be wearing a wedding-white three-piece suit with his two-toned shoes on the creamy-white album cover. I think he uses the image of a wedding to communicate an imperfect reunion of the world stage after the war. The innocence of this pre-World War II time is a ghost to those of us born long after both wars.

Graham Greene is another musical oddball – the closest to reggae a Welshman can get. John sounds a little silly barking these words out over this jaunty instrumentation, it’s got marimba and everything. He admitted this was the first thing he wrote after deciding he’d exclusively work on classical music..cocaine is one hell of a drug.

The longest song on the album, Half Past France, stands on well-paced, intricate guitar work by Lowell and a droning organ from John. A lot of people seem to interpret this song being about a traveler, on a train “halfway between Dunkirk and Paris.” I think it’s about being halfway between Dunkirk and Paris. Halfway between war and peace, uncertain of how things will end. This is bolstered by the narrator bearing a positively wartime mindset:

“But from here on, it’s got to be

A simple case of ‘them or me,’

If they’re alive, then I am dead

Pray God and eat your daily bread.”

In this context, mentions of such faraway locations as Norway, Dundee, and Berlin make sense. This man is a traveler, yes, but a traveler in the sense the narrator of “The Partisan” is a traveler. “There were three of us this morning, I’m the only one this evening,” “I have changed my name so often/I’ve lost my wife and children.” “I’m not afraid now of the dark anymore/And many mountains are now molehills,” “Wish I’d get to see my son again…”

This song may be also about John himself; the man always searching for something more. But no city, business move, or wife can quench his thirst for adventure. It’s a lonely existence being a seeker. “Half Past France” is a hymn to whichever past life we know we can never return to, whether a life before wartime or the comfort we once felt in our circumstances. The church organ swelling at the end is just gorgeous.

I would’ve loved to have “Half Past France” as the closer, setting us off on some great journey into the unknown. But I’d be silly to refuse Antarctica Starts Here. John uses a warmer, fuzzier, decidedly seventiessound on the organ. His voice is left battered by substances, exhaustion, or both. It makes a lament of a woman’s lost beauty and time sound intimate, and hauntingly beautiful. John’s voice cracks as the powder does on her wrinkled skin. An accordion kicks in, but for just a moment: the chords destabilize themselves. John’s whispering pitters off and the song lifts away like a dream as you wake up from an afternoon nap. The golden sun shimmers, but doesn’t feel as warm as it once did. Paris 1919 is a pretty, if worried and terribly lonely album.

Pisces is the sign of the fish; two fish swimming in opposite directions. Both Lou and John are Pisces. Lou was the fish swimming up. Bizzaro as his excursions could get (Metal Machine Music, Lulu and the infamous “I AM THE TABLE!!” etc.,) Lou had the radio rock-and-roll background. He had appeal - in his own twisted way.

John is the fish swimming down. The dark star, he has a magnetism about him. Not charisma. Magnetism.They’re different. He’s refused to do the same thing twice, always searching for some outer bank. This got cut from my Beatles: Note By Note appearance, but at the top of the episode, Adam and Kenyon asked me which rock stars I find hot. They were asking about like, Robert Plant and Jim Morrison and whoever else. And I was laughing and saying you’re not just barking up the wrong tree, you’re in the wrong forest!! Sensing an affinity for “edge,” one of them asked what I thought of Lou Reed. I said “No, John Cale.”

Unlikely as it may seem at a glance, there’s a thruline of all the men I’ve been infatuated with; the rock stars I like and men I go for in my real life. The ones who shove their guitars in front of amps, can hold their own with Sun Ra, the ones invoking some primal otherworldly shit when they sing. The ones who refuse to do the same thing twice, and the ones dressed in black; sitting in the corner with a hank of dark hair over their face as the smoke pours out of their cigarette. What an asshole, what a little shit. They just don’t understand you, subversive one. I want the fish that swims down.

I would call Astral Weeks a distant cousin of this album in the sense that they’re both ethereal, impenetrable, and deeply feeling. Plain and simple, Paris 1919 is fucking stunning. The production is top-notch – I’d expect nothing less from a man who is a producer himself. Its sound is velvety soft and thick. A little country, a little classical, a little pop, a little rock-and-roll. The players fill out John’s elusive writing with a lush, warm-spiced sound. This is such a winter album – “A Child’s Christmas,” “When can I see ya?/When it is snowing out again?” “Antarctica Starts Here.” Even the album cover is white like show. But Paris’s warm ephemeral moments feel warm like cinnamon in your chest, or remembering summer; hoping for the warm sun to kiss your hands again. But the cold, oh man. Paris 1919 has the weight of an old man looking through his photo albums and finding he never stopped grieving his first wife. It’s amazing that an album written by a thirty-year-old can bear the weight of a man of 100.

john cale paris 1919

This is like no other album John released. Sure, you could say that about any of his albums! But this one especially. He tries to hide his heart on Paris with ornamental instrumentation, strings and bells, literary references, and lyrics obscured by their own wording. But I see right through him. After drawing those heavy curtains back, I’ve found this might be John’s most personal work. He tells of nostalgia, dissociation, loving, and loss. He expresses the eternal unrest that lies in your heart when you’re an artist; the drive behind all his work for nearly sixty years. Always being in search of something, but not knowing what it is. It’s as unattainable as the fish swimming down, the dark star on the outer band of our galaxy. It’s ghostly. Once you think it’s in your grasp, it’s gone. It’s hard loving the restless soul because once we feel that urge for going, you can’t stop us. Best to enjoy Paris 1919 while it’s in your arms, before it slips away again into the cold winters’ night.

Personal favorites: “A Child’s Christmas In Wales,” “Andalucia,” “Paris 1919,” “Half Past France,” “Antarctica Starts Here”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Bockris, Victor. Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story. London: Harper Collins, 2014 ed.

Boyd, Joe. White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. London: Serpents Tail, 2006.

Cale, John, with Victor Bockris. What’s Welsh For Zen: The Autobiography of John Cale. New York: Bloomsbury, 1999.

Evans, Kim, dir. “The Velvet Underground.” The South Bank Show. 1986. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1sbg_C-72c

Holden, Stephen. “Paris 1919.” Rolling Stone, 5/10/1973.

Unterberger, Richie. White Light White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day. London: Jawbone Press, 2023 ed.

i'm thinking that Mick Ronson's contributions were a little toooo good in terms of him being a collaborator. discuss.

a very beautiful example of the coming together of classical style orchestration and rock band ( do they ever truly integrate idk) is the Barclay James Harvest song mocking bird. see i want the yearning to be in the music, the notes.

i really went for this album though. it's varied in the sense of soundscapes and of landscapes. i was thinking of lautrec posters for the lettering but maybe, AD, you were thinking of some other album cover.

the attractiveness of deep characters, the necessity of turning a few pages before you get them, is mirrored by your writing and…

Interesting note on Cale. He and John Cage both made separate appearances in the early 60s on the American gameshow “I’ve got a secret” (found the video of both on you tube) and at the time, Cale had recently completed a concert in NYC where he was one of the pianists, along with Cage, who produced the concert. Multiple pianists at the concert played Eric Satie’s “Vexations” 840 times. It took 18 hours! That’s pretty cool.

Great review! Loved what you said near the end about being ghostly, once you think it’s in your grasp it’s gone, reminds me of the Comfortably Numb lyric “saw a fleeting glimpse out of the corner of my eye, I turned to look and it was gone”, or like a dream you had that you want to fall asleep again to find but never can.