Bruce Springsteen - Born To Run, 50 Years Later

- Abigail Devoe

- Aug 25, 2025

- 19 min read

If you thought this was your last shot, what would you do? Would you sulk off back where you came from, or would you keep running?

With Born To Run, Bruce Springsteen kept running.

Bruce Springsteen: lead vocals, guitar, harmonica

E Street Band:

Roy Bittan: piano, organ, percussion

Gary Tallent: bass

Max Weinberg: drums

Clarence Clemons: saxophone

Danny Federici: organ, piano on “Born To Run”

Davy Sancious: piano on “Born To Run”

Ernest “Boom” Carter: drums on “Born To Run”

Steven “Little Steve” Van Zandt: horn arrangement, “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out”

Richard Davis: double bass on “Meeting Across The River”

Michael Brecker, David Sandborn: saxophones on “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out”

Randy Brecker: trumpet on “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” and “Meeting Across The River”

Suki Lahav: violin on “Jungleland”

Produced by Bruce Springsteen, John Landau, and Mike Appel

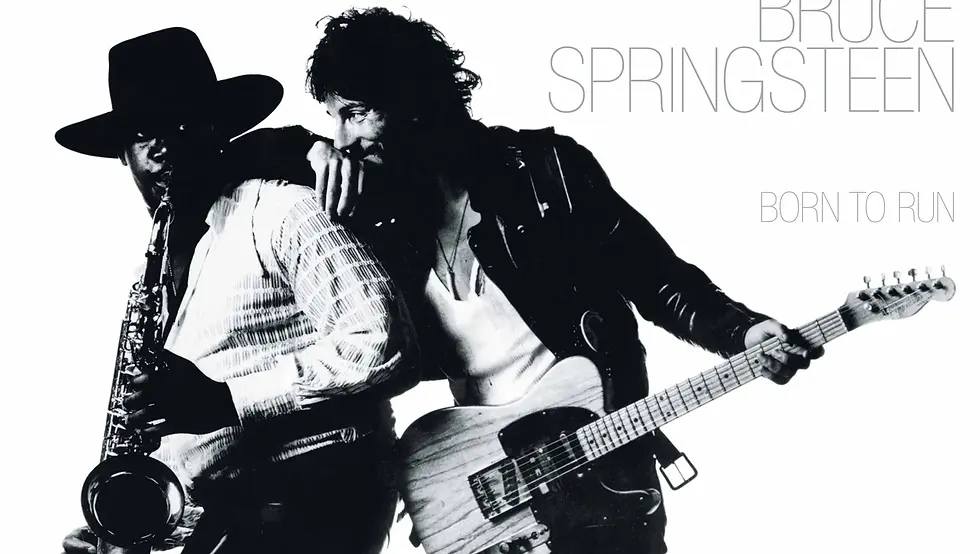

art by Eric Meola

In the words of biographer Peter Ames Carlin, “...like the characters in ‘New York City Serenade,’ Bruce still splayed between triumph and collapse.”

It’s the winter of 1974. Rolling Stone gave a glowing review of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band’s sophomore effort, The Wild, The Innocent, & The E Street Shuffle. Ken Emerson wrote, “The best of (Bruce’s) new songs dart and swoop from tempo to tempo and from genre to genre, from hell-bent-for-leather rock to luscious schmaltz to what is almost recitative. There is an occasional weak spot or an awkward transition, but for the most part it works spectacularly…” Radio DJs in Cleveland and Philadelphia went to bat for Bruce; making “Rosalita” a local hit in both cities. They earned a small, but loyal fan base in the northeast, and a handful of famous fans including Lou Reed and Robert De Niro. The E Street Band were killer live; so undeniably good that Jackson Brown’s manager wrote to the higher-ups asking not to book Bruce on the same bill, for fear of his guy being outshined!

But E Street Shuffle didn’t sell as Columbia had hoped. They’d hyped Bruce up as “the next Bob Dylan.” Had they learned nothing from Badfinger, Crosby, Stills & Nash, T. Rex, and ELO all being hyped as “the next Beatles?” Or Donovan being hyped as “the next Dylan,” for that matter? In his book Magic In The Night: The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen, Rob Kirkpatrick identifies, “...by early 1975, Bob Dylan had arrived twice, while the man once pegged as the next Dylan had yet to arrive once and was still toiling in relative anonymity…”

Clive Davis was Bruce’s biggest ally at Columbia, but he’d left. Enter Charles Koppelman and his piano man, Billy Joel. Proved more marketable than the maximalist, eclectic E Street Band. There were serious talks of dropping Bruce after the third album of his deal; triggering a power struggle between the execs. Half of Bruce’s production team left when Jim Cretecos sold his shares in the business to co-manager Mike Appel.

Mike was...quite the personality. His hail-mary attempts to get Bruce on Columbia’s good side included bookinghim at a venue down the street from the execs’ hotel in Nashville, and sending stockings of coal to DJs that refused to play his stuff! Even he’s losing hope; debt collectors are banging down his door. The drama in the exposition alone is enough to make a Scorsese film! And Scorsese agreed! He tried to cast Bruce in one of his movies!

Columbia gave Bruce the budget for one more single. If it performed, his band could stay. If not, he’d take a hike.

“I wanted to craft a record that sounded like the last record on earth...the last one you’d ever NEED to hear.”

quoted from: Bruce Springsteen, Born To Run (2016.)

Our tight white t-shirt-wearing hero aching from a breakup, holed up in a cottage in West Long Branch, New Jersey. Through this bitter winter of 1974, he studied the radio hits of his childhood. Of course, he’s a Bob Dylan devotee, but early ’60s pop is on his mind. He wants to channel Phil Spector’s work with the Ronettes, and the stylings of Roy Orbison. “The darkly romantic visions of both Spector and Orbison felt in tune with my own sense of romance, with love itself as a risky proposition. These were well-crafted, inspired recordings, powered by great songs, great voices, great arrangements, and excellent musicianship.”

Bruce doesn’t remember where the phrase came from exactly, but it fit with the lyric, worked with his vision, and reflected the dire straits he was in. “I liked it because it suggested a cinematic drama I thought would work with the music I was hearing in my head.”

Work on Bruce’s suicide-rap single, what would become the centerpiece of his next LP, began on January 8th, 1974. When the lyrics of “She’s The One” were repurposed into “Backstreets,” the ball was rolling on an album.

If work started in January of ’74, how come we didn’t hear it until August of the next year?

It’s the stuff of rock-and-roll legend: the title track alone took six months to make.

This was in part because of Bruce’s touring schedule. They needed the money to cut this thing, and it sure wasn’t coming from selling the records! The E Street Band popped into 914 Sound Studios in New Yorkwhenever they could. Drummer Vini Lopez didn’t even make it to “Born To Run” sessions. He was fired after punching Little Steve in the face.

When one door closes, another opens. “It was a winter’s night in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I stood on the street in front of our gig, Joe’s Place...I was reading a review of our second album; the owner had taped it to the front window in hopes of luring in some breathing customers. Then two men walked up on my left.”

One of the men was Dave Marsh of Creem, the other was Jon Landau of Rolling Stone. (Yes, the guy who wrote that Beggars’ Banquet review mentioning the MC5, then produced Back In The USA less than two years later!) He was there on assignment to write a review of Bruce’s Cambridge gig. This is not hyperbole, the gig restored Landau’s will to live. He wrote,

“On a night when I needed to feel young, (Springsteen) made me feel like I was listening to music for the first time. I saw my rock and roll past flash before my eyes. And I saw something else. I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.”

quoted from: Peter Ames Carlin, Bruce (2012.)

What you need to understand about the music industry before about ten years ago was that one review could make or break your whole career. See Jon Landau’s review of a Cream gig effectively breaking up the band! Landau’s review kicked Columbia’s asses in gear. They leaned into the hype surrounding Bruce. Good in theory, but only adds to this make-or-break feeling.

“Born To Run” was a feat of recording technology to make. This thing was overdubbed to hell. According to Bruce, to accommodate the recording technology of the time, 72 tracks had to be mixed down to fit onto sixteen. Not to mention the five versions of the lyrics!

“I worked very, very long on the lyrics of ‘Born to Run’ because I was very aware that I was messing with classic rock ’n’ roll images that easily turn into clichés. I kept stripping away...cliché, cliché, cliché...I just kept stripping it down until it started to feel emotionally real.”

quoted from: Bruce Springsteen Wings For Wheels – The Making of Born To Run (dir. Tom Zimny, 2005.)

The title track was at first rejected by exec Irwin Segelstein, on the grounds of it being “too long” for FM radio.Bruce Lundvall, though, was just about blown out of his chair. He told Bruce straight-up that he had a hit on his hands.

Now that “Born To Run” was in the can, “Jungleland” was giving them trouble. Sessions were plagued by a truly comical amount of equipment malfunctions and interruptions. “The scene played like a joke about a perfectionist being driven mad. Only none of it seemed remotely funny.” Landau saw the band’s plight and stepped up; he oversaw the rest of Born To Run sessions at the Record Plant’s location in New York.

Columbia issued a deadline, tour was booked. It was now or never. As the story goes, when Bruce heard the acetate for the first time, he frisbee’d it into the hotel swimming pool! It took Mike Appel, his brother and Bruce’s tour manager Steve, and Landau all to talk Bruce out of scrapping the whole thing.

Bruce seems to remember the title track coming out as a months before the album’s release, but looking at chart data, it was only officially released on album release day. According to Rob Kirkpatrick, it was Mike who leakedtitle track months before in hopes of generating buzz! Landmark shows at the Bottom Line and its rave reviews only got the hype train moving faster. Bruce was on the cover of Time and Newsweek in the same week. Columbia threw a quarter of a million dollars into promotional efforts…

...and it worked. The peaked just under the top 20. Astonishingly, Bruce had no number one hit in his career (“Dancing In The Dark” peaked at number two.) Where E Street Shuffle didn’t chart at all, Born To Run peaked at number three on the Billboard albums chart.

I’ve been thinking of something John Lennon said to Paul McCartney during Get Back sessions: “When I’m up against the wall, Paul, you’ll find I’m at my best.”

Bruce makes the best music when the stakes are high, he witnesses injustice in the world, or he feels backed into a corner. All of these circumstances conspired to make Nebraska happen. That’s exactly how Born In The USA happened. This is the core essence of Bruce Springsteen; knowing the “American dream” is unattainable, now more than ever. But still having hope, because what other option is there? Giving up? That’s way worse! Might as well lay it all out on the line.

The “last album ever” thing reminds me of what the Clash would do with London Calling a few years later. When the stakes are high, you put it all on the line and try risky stuff you might not otherwise. Bruce operated like Born To Run would be the last album he’d ever make, because for all he knew, it might be.

As far as sound, Born To Run is also quintessentially “Bruce.” Piano, bells, saxophone, his marble-mouthed and rousing “Jersey-Pavarotti-via-Roy Orbison” wails. More-is-more. All drama and despair. From here, we either elaborate on it, ’80s-ify it, or strip it down to the studs.

I was skeptical about Born To Run. I remember feeling the same going into Born In The USA last summer. Coming from the music I typically like, this mid-’70s maximalism is all so...cheesy, right?

How does Bruce’s music achieve such drama?

Of course, there’s his delivery. I believe he’s an underrated vocalist in this sense. Carlin:

“...the stereo speakers boil over with romantic urgency. Even when the lyrics glow purple (the killer in the sun, the talking guitar, the screaming ghosts,) the belief in Bruce’s voice keeps it riveting. Bruised, burned, and somehow unbowed, he’s taking the American ideal at its word, betting it all on the open road and his own stubborn will.”

quoted from: Peter Ames Carlin, Bruce (2012.)

The real secret ingredient to 150-proof Bruce is that Born To Run was primarily written on piano. A piano can play more notes than a guitar can; opens up the possibility for dramatic melody and grand, sweeping girl-group arrangements. It’s the backbone of the whole thing; the secret ingredient of peak “Bruce.”

Born To Run opens with a harmonica – you’re not beating the Dylan allegations, Boss! – and piano that lifts and carries us into Thunder Road. “Thunder Road” is already such an evocative title. Modern listeners don’t understand just how central cars were to youth culture in Bruce’s youth, the 1950s and ’60s; especially in the working class. My grandparents skipped their high school prom to go to the racetrack!

Though her name changes from Mary to Wendy to Cherry, Bruce writes in his memoir that he considers Born To Run the story of one couple in spirit. “The screen door slams, Mary’s dress sways/Like a vision, she dances across the porch as the radio plays.” Love at first sight. There’s the obligatory shout to Roy Orbison in the next line, and the picture starts to come into focus.

“So you’re scared and you’re thinking

That maybe we aren’t that young anymore.

Show a little faith, there's magic in the night,

You ain't a beauty, but hey, you're alright...”

“Thunder Road” says, “We’re not teenagers anymore, we’re not Hollywood good-looking. But I have a guitar and a car and we can try our hand at the great love we were promised once.” What’s the other option, “Waste your summer praying in vain for a savior to rise from these streets?” Here he is! Musically, “Thunder Road” introduces all the Bruce tropes: grand piano with the ’50s rock-and-roll swaths, ’70s-does-’50s guitar, tumbling excitable drums, and of course, a saxophone. If you don’t like saxophone in your rock-and-roll, bow out now! Clarence’s solo was moved to the end of the song per Landau’s suggestion, I think this was the right call. It gives the song an end goal, a place to go.

The totally drive-in-ready Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out was helped along by Little Steve. He was a fellow early ’60s freak, he even dated Ronnie Spector after she divorced Phil! At first, teh lyrics don’t do much besides paint a picture of a typical night in this community. Transistor radios in a tenement window and tough-guys galore. Then, “Freeze Out” becomes the story of the E Street Band. “When the change was made uptown and the Big Man joined the band,” then Clarence jumps in with a little sax lick. The “Big Scooter” in the song is Bruce himself.

It’s a little homage to their bromance; what the band ran on. I wish we’d gotten a little more out of the tempo push at the very end; like the diner bursting to life when the right song comes on over the jukebox.

Lyrically, Night doesn’t stand out from the bunch. It’s more about a guy and his car longing for his lady to come along and shake up his life. This song is swamped out by the sheer power of the other greats on this album, but I’ll give kudos to Gary Tallent’s bass playing. The energy comes from him.

Backstreets isn’t one of my favorites on the album either. There’s a point where the maximalism and sappy piano becomes too much for this listener. I’m always intrigued by the ambiguity of its narrative. Other listeners have interpreted it as a love song – considering the sheer intensity, it’s easy to mistake it for such – but “Backstreets” continues the Bruce tradition of songs about friendship between boys in their formative years. We’ve heard some about the danger of romantic love, but when you’re teenagers on your own for the first time, the whole world is that exciting and dangerous. When you’re no-good outcasts, all you have is your closest friend to watch your back. Bruce’s repetition of the line “Hiding on the backstreets” as the drums get bigger and the guitar lets loose into its full grandeur is my favorite part of the song. The drama worked through tension and release, and Bruce emotes that line slightly different every time.

And now, for the moment you’ve all been waiting for. The side two opener. The “wide-screened rumble” of Born To Run. Rob Kirkpatrick called the song “deceptively simple.” Maybe it’s because I know the lengths guys like Spector went to achieve that wall of sound, but I thought, “‘Born To Run’ is ‘simple?’ In what world??”

From the music itself to the story Bruce tells, it’s quite layered. Let’s start with the first singular second of the song. “Born To Run” was Boom Carter’s one and only appearance on an E Street Band album; he whips out an urgent drum roll worthy of the Wrecking Crew. About that roll, he said, “Now I’m a part of rock history – and I wasn’t even trying.” The song bursts into the thumping drums, driving 50s rock-and-roll piano chords, and the bells. The bells! The tail-end of the core guitar motif is a nod to Duane Eddy’s “Because They’re Young.” The heavy reverb made me think of another early rock-and-roll guitar hero: Link Wray.

If we’re talking early rock-and-roll, we can’t forget a saxophone. Saxophones used to be a staple in pre-Beatles rock-and-roll. I think what makes this wall of sound approximation “work” is its lack of big, booming drums. If “Born To Run” had everything, it’d feel like parody.

These lyrics should not work. They are so loaded with cliché. Working away the days, going out driving at night, enticing Wendy-Mary-Cherry to run away with you. The magic lies in this one line; the thesis statement of Bruce’s whole career:

“I wanna know if love is real.”

When you’re from a working-class community without a lot of upward mobility and without many places to go, you set your personal hopes aside in favor of paying your fucking bills. “Maybe this town rips the bones from your back/It’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap/We gotta get out while we’re young.” Do or die, babe. The longer you stay, the harder it is to leave. Being an adult is a dreary world, especially in our isolated modern age. You yearn for connection; some great sweeping feeling to escape to. The love you envisioned – or maybe had – as a teen. I can only imagine what this is like for the men, who society teaches to cauterize their emotional wounds in favor of macho-man stoicism. Love is vulnerable, love is dangerous. “Will you walk with me out on the wire? ’Cause baby I’m just a scared and lonely rider.” I think this is why men find themselves crying at Bruce shows the way us girls can cry at most any show. It’s cathartic to feel, and be in a room full of people doing the same.Hear how Bruce empties every last drop of his breath into this. He can’t help but burst out in these “OOOH!”s.

With that line, “I wanna know if love is real,” Bruce openly longs to take the vulnerable, dangerous leap: leaving this town with that girl. He follows it up softly with, “Oh, can you show me?” It’s seductive! The whole verse before it is. “Wendy let me in, I wanna be your friend/I wanna guard your dreams and visions.” It’s a verytraditionally masculine idea; wanting to be the big protector. “Just wrap your legs round these velvet rims and strap your hands ’cross my engines...” wink-wink. Why does the girl go for the guy with the motorcycle? Because danger is sexy! This is shaping up to be the ride of a lifetime, even after they’ve reached their destination.

It sounds like our hero and heroine have won. They make their great escape as the town peels out behind them. The arrangement pulls back to piano, bells, and drums (just goes to show how much was going on before for such a grand three instruments to be considered “pulling back.”) The guitar is affected, like scenes melting awayin chrome fenders. “Girls comb their hair in rearview mirrors/And the boys try to look so hard,” classic drive-in scene. “The amusement park rises bold and stark,” kids are huddled down on the beach in a mist. “I wanna die with you Wendy on the street tonight/In an everlasting kiss.” If the “I wanna be your friend” verse was Bruce’s interpretation of Romeo and Juliet’s balcony scene, this is the end. The music kicks in full gear with feverish, rousing excitement, the bass chugs along. It all tumbles down into an anxious stop; keys and piano waiting for their cue to sweep back up again. It sounds like a rumbling engine. Apparently, Bruce wanted a “Leader of the Pack”-style motorcycle sound here. Then,

“The highway’s jammed with broken heroes

On a last-chance power drive,

Everybody’s out on the run tonight,

But there’s no place left to hide.”

Imagine thinking you’re the only two people in the world who could possibly feel this way about each other, and you finally get on the highway out of that town, only to get stuck in a traffic jam of hundreds of couples just like you. It’s tragic, really.

The strings emphasize such. It’s your choice to keep finding new things about each other to fall in love with. Either you feel safe and close up inside, ending the trip for good, or you keep running.

The song closes perfectly; with Bruce’s nod to Ronnie’s signature “Woah-oh-oh-oh,” and a fadeout that leaves you longing for just one more second of it; just one more whiff of her hairspray and perfume. Though the formula would be copied over and over, from Bon Jovi to U2 to the Killers, not even the Boss himself could replicate the magic of “Born To Run.”

How the hell do you follow that up?

She’s The One opens side two with soft electric guitar strums; as if sitting on a hotel room bed after “Born To Run”’s great escape. Keeping with this hotel image, as his lady comes back from taking a shower or getting ice, our narrator simply reflects on her beauty. Her French cream, her French kisses, her long hair and intense eyes. He’s simply marveling in her beauty, but struggles to allow himself the vulnerability. Such is one of the core struggles of Bruce Springsteen’s writing. “French cream won’t soften them boots/And French kisses won’t break that heart of stone.” “She can take you, but if she wants to break you/She’s gonna find out that ain’t so easy to do.” I love the Neumann-mic-leak on Bruce’s voice. It sounds as if he’s singing to himself in an empty room, though the keys and piano whirl around them. When the song builds into a hand-clapping jive and we addanother layer of echoing vocals, it still retains its intimacy.

“She’s The One”’s hesitant tenderness bursts into sheer fun. The blasts in the back half of the song are just fun!The piano rolls along, and drums batter up layers of swing-dance-dress crinoline. Bruce revealed that “She’s TheOne” was written just for Clarence to play on. Hearing that back-and-forth between him and the lofty, “Ohh, she’s the one!”s gets one moving; on your own or with your lover.

I was very surprised to learn the E Street Band were so into Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. According to Little Steve, Meeting Across The River was directly inspired by it. This album was “was like a religion” to them; hence Astral Weeks double-bassist Richard Davis making a cameo. Beginning with its echoing, jazzy trumpet and sparse piano, “Meeting” is a sobering moment on Born To Run. The excitement, danger, and passion melts away into a very real moment.

“Hey Eddie, can you lend me a few bucks tonight? Can you get us a ride?” Never has it occurred that our couple might really be running from something. The feeling was always that they were escaping invisible confines rather than real danger. They’re tangled up in some business bigger than them. There’s talk of money on the bed and stuffing something in your pocket to make it look like you’re carrying. “They’re” looking for our narrator. Though he asserts “this guy” is “the real thing,” the secrecy and setting of a dark, damp tunnel tells the audience he isn’t. I never felt there’d be an end to this love story, let alone a tragic one, until now.

Born To Run closes with Jungleland. This number took three times as long as “Born To Run” to record, and I hate to report it sounds like it. I can hear the stress and strain come through in the quiet bits, and not in that Bruce way that makes me feel what his characters feel. When the arrangement fills out with more rock instruments – and the string effect on the keys is less noticeable – I can be immersed in the story. Suki Lahav’s romantic violin introduces the tale of the Magic Rat and his barefoot girl on the hood of the Dodge. Mary, Wendy, or Cherry. Twin shrieking guitars paint all sorts of grit and excess, “the hungry and the hunter” and kids flashing guitars like switchblades. It’s all beehives, radio DJs, and hot rods. The optimism we felt in “Thunder Road,” “Born To Run,” even “She’s The One” is put to the test by the harsh realities of “Meeting Across TheRiver” and “Jungleland.” We don’t know what becomes of this couple, but if the song before and the line, “The Rat’s own dream guns him down” are any indication, it’s not looking good.

“Outside, the street’s on fire in a real death waltz

Between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy.

And the poets down here don’t write nothin at all,

They just stand back and let it all be.”

Against the piano, Bruce delivers, “And in the quick of the night, they reach for their moment and try to make an honest stand” with all the conviction of a black-and-white movie leading man. But the dream falls apart. “Wounded, not even dead.” They don’t get the satisfaction – the glory – of being gunned down in a fabulous blaze like the Rat. They’re just ordinary people. Twirling piano and cinematic falls give way to one of Bruce’s great wails; given all the space it needs to work. A strained, wounded howl with the slightest hint of wet vibrato; the final cry of the man who’s fought tooth and nail for this. And scene. Roll credits.

American Graffiti and Born To Run were the first notable musical throwbacks to the boomers’ childhoods. They mean something for similar reasons. Bruce took the iconography of ’50s rock-and-roll – the leather jacket, the white shirt, the guitar, the cars, the girl – scored by a double-whammy of ’60s wall of sound maximalism and Dylan’s Highway 61-era swagger, all set against the grit and despair of post-Watergate 1970s working-class America. 1975 wasn’t just a weird year for music, it was a weird year for America. The chaos of the ’60s, Bruce’s teenage years, left the innocence and optimism Eisenhower era promised thoroughly dead and gone. There were still six months to go until America’s bicentennial year. Watergate still fresh in peoples’ memories – not to mention Ford pardoning Nixon the summer before. In the words of Red Forman, “How the hell could you pardon Nixon?!”

About the characters of Born To Run, Bruce said:

“...the dream we had of ourselves had somehow been tainted and the future would forever be uninsured...if I was going to put my characters out on that highway, I was going to have to put all these things in the car with them.”

quoted from: Bruce Springsteen, Born To Run (2016.)

Amidst all the chaos, you have this guy prancing around stage in tight white t-shirts and even tighter jeans; blending the tropes and sounds of rock-and-roll with a post-Nixon self-awareness, delivering it all with such conviction and a fierce display of brotherhood amongst his backing band. If you thought this was your last shot, what would you do? Would you sulk off back where you came from, or would you keep running?

Sure, we know it’s Hollywood. We know the story of the car and the girl isn’t real. But it’s hard not to be swept up in all that, and see our own stories play out on sweaty brows that flash across that big screen. Blood, sweat, and tears, Bruce invites you to suspend your disbelief and get invested the way you did when you were young. You can bring your world-weary perspective in, you have 40 minutes to surrender to feeling.

It could reflect your circumstances. It could have you stewing on your tragedies. Who doesn’t cry at the end of a good film? 50 years later, Born To Run still makes a bid to convince even the stoniest of hearts that maybe...love is real

Personal favorites: “Thunder Road,” “Born To Run,” “She’s The One,” “Meeting Across The River”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Carlin, Peter Ames. Bruce. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Emerson, Kevin. “The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle.” Rolling Stone, 1/31/1974. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/the-wild-the-innocent-the-e-street-shuffle-247900/

Hiatt, Brian. “Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born To Run’ Turns 30.” Rolling Stone, 11/17/2005. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bruce-springsteens-born-to-run-turns-30-57678/

Kirkpatrick, Rob. Magic In The Night: The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2009.

Marcus, Greil. “Born To Run.” Rolling Stone, 10/9/1975. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/born-to-run-87675/

Masur, Louis P. Runaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen’s American Vision. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Springsteen, Bruce. Born To Run. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Zimny, Tom. Bruce Springsteen Wings For Wheels - The Making of Born To Run. Thrill Hill Productions, 2005.

will it MC 5 yes it will!

that picture building " with all the conviction of a black and white movie leading man. but the dream falls apart " is terrific. i enjoy your writing so much even if I'm a bit removed from the music.

if ever you've worked one of those giant flat bed printing press's in art school, turning the big wheel, then that's the sense i'm left with listening bruce's music. he puts an effort in we put an effort in. but it's a massive ongoing career and there are very good songs.

but y'know as a songwriter once said (possibly as a direct riposte i'm not sure) "something's hurt more much more than cars and…